Beyond the fourth dimension

Coxeter, like Forsyte's character "Old Jolyon", "ached a bit from sheer love of it all,

feeling perhaps, deep down, that he had not very much longer to enjoy it. The thought that

some day - perhaps not ten years hence, perhaps not five - all this world would be taken

away from him, before he had exhausted his powers of loving it, seemed to him in the

nature of an injustice, brooding over his horizon. If anything came after this life, it

wouldn't be what he wanted."

Commentary on the last years of Coxeter's life in "King of Infinite Space: Donald Coxeter,

the Man Who Saved Geometry", by Siobhan Roberts.

What happens at dimensions higher than 4?

Regular polytopes

Before moving on, we need new terms when discussion polytopes in many dimensions. The

general equivalent of a face in a polyhedron and a cell in a polychoron is a facet. This is the

highest-dimensional element of the surface of a n-dimensional polytope (henceforth, a

n-polytope), thus having n−1 dimensions. This is also the case for the vertex

figures. The ridges

are n−2-D elements of the n-polytope's surface. This is also the case for the

edge figures. In a regular polytope, all surface elements of a particular dimension are

not only identical, but the polytope also looks identical as seen from each instance of

those elements. This implies that each of the n types of element corresponds to a

particular overall n−1-D symmetry of the polytope.

In Euclidean spaces with more than 4 dimensions, the only regular polytopes are the

aforementioned simplices,

hypercubes and their

duals, the cross

polytopes, or ``orthoplexes", making therefore a total of 3 regular polytopes for each

Euclidean n-dimensional (henceforth n-) space. These polytope families are infinite, with

members in all n-spaces. There are no analogues of Icosahedra/Dodecahedra or

600-cell/120-cell, there are no regular star polytopes either, and nothing like the

24-cell, which exists only in 4-D Euclidean space. In this way, one comes to appreciate

the fact the latter are exceptional objects.

We now enumerate the basic characteristics of these families that will be important for

understanding what follows, with 3-D examples in parenthesis:

- Regarding the simplices, they always have the smaller number of elements possible for

a polytope in their n-space. The n-simplex (e.g., a Tetrahedron, ...) is built from a

n−1-simplex A (Triangle A) with side ℓ by adding a single point outside A's

n−1-D hyperplane, at distance ℓ from all vertices of A (... a pyramid apex,

where Triangle A is the base), and linking that point to all the others with n other

n−1-simplices (... n = 3 additional Triangular faces). Thus, the n-simplex has n+1

vertices, n+1 facets, and both the facets and vertex figures are n−1-simplices. They

are therefore self-dual. They have no central symmetry.

- The n-orthoplex (e.g., an Octahedron) is built from a n−1-orthoplex A (Square A)

with side ℓ by adding two points, P1 and P2, in a line perpendicular to A's hyperplane

at distance ℓ from A's vertices, one of them above and another one below A's

hyperplane. Then those points are linked to A's vertices using n additional

n−1-simplices for both P1 and P2, thus doubling the number of facets of A (... 2

× 4 = 8 Triangular sides). Importantly, P1 and P2 are not directly linked to each

other. In this process A becomes an equatorial polytope. This implies that orthoplexes

have 2n vertices and 2n facets.

- The n-dimensional hypercube, or n-cube (e.g., a Cube) can be built from a

n−1-cube A (Square A) with side ℓ by adding an identical n−1-cube, B, at

distance ℓ from A along a perpendicular direction (... a second Square); this doubles

the number of vertices. Then, A and B are connected with n−1-cubes, as many as the

number of facets of A and B (... four additional Squares), in hyperplanes perpendicular to

those of A and B. Thus, the number of facets grows by two with each dimension, their

number is 2n; the number of vertices is 2n.

The n-orthoplex is the dual of the n-cube. They therefore share the same symmetry,

which includes central symmetry. The n−1-simplex facets of the former correspond to

the n−1-simplex vertex figures of the latter. The n−1-hypercubic facets of

the latter correspond to the n−1-orthoplex vertex figures of the former. Since only

the latter elements have central symmetry, only the orthoplexes have equatorial polytopes

and only the Hypercubes have the dual equatorial facet rings. The n-orthoplex has an

equatorial n−1-orthoplex between any two opposite vertices, their number is

therefore 2 n / 2 = n.

***

We now present some Zomable projections of higher dimensional regular polytopes into three

dimensions. Apart from their intrinsic interest, studying these projections will improve

our understanding of projections of polytopes in general, and will add new understanding

of the models of the 4-dimensional polychora as well. In all these models, the white

connectors indicate real vertices, the other colours denote edge intersections that happen

because of the projection, not in the polytopes themselves, which are all convex.

We start with the simplexes. When projecting a n-simplex into 2-D space, we can always

arrange the direction of the projection in a way that the vertices are all equidistant

from the centre. The reason is that, as we've seen above, when we build the n+1-simplex,

we add a new vertex that lies on a line perpendicular to the n-simplex and is equidistant

from all its vertices. Thus, if we project the n-simplex into 2-D space along that

perpendicular line, then all its vertices must lie at the same distance from the centre,

making an "equidistant" projection. Furthermore, they and their connections to other

vertices must look identical independently of the vertex, this implies a symmetric

projection. Their distribution would be a regular Polygon with n+1 sides. To make a

symmetric projection of the n+1-simplex, there are two easy options: one of them would be

to use the same projection vector and project the new vertex to the centre, making a

vertex-centred projection, or project all vertices as the vertices of a n+1 Polygon.

For projections into three dimensions, the logic is the same, except that we can't find

symmetries with an arbitrary number of vertices. For instance, for the 4-simplex, which

has 5 vertices, there is no symmetric distribution of all vertices around the centre: what

was done in Fig. 5.3 was to use a symmetric distribution of vertices of the 3-simplex (the

Tetrahedron) and project the new vertex to the centre, thus making a vertex-centred

projection. The other Zomable projections of the 5-cell (Fig. 7.8) have a lower symmetry.

However, the 5-simplex

has 6 vertices and 6 facets; this means that we can make an equidistant projection, where

the vertex arrangement is that of the Octahedron.

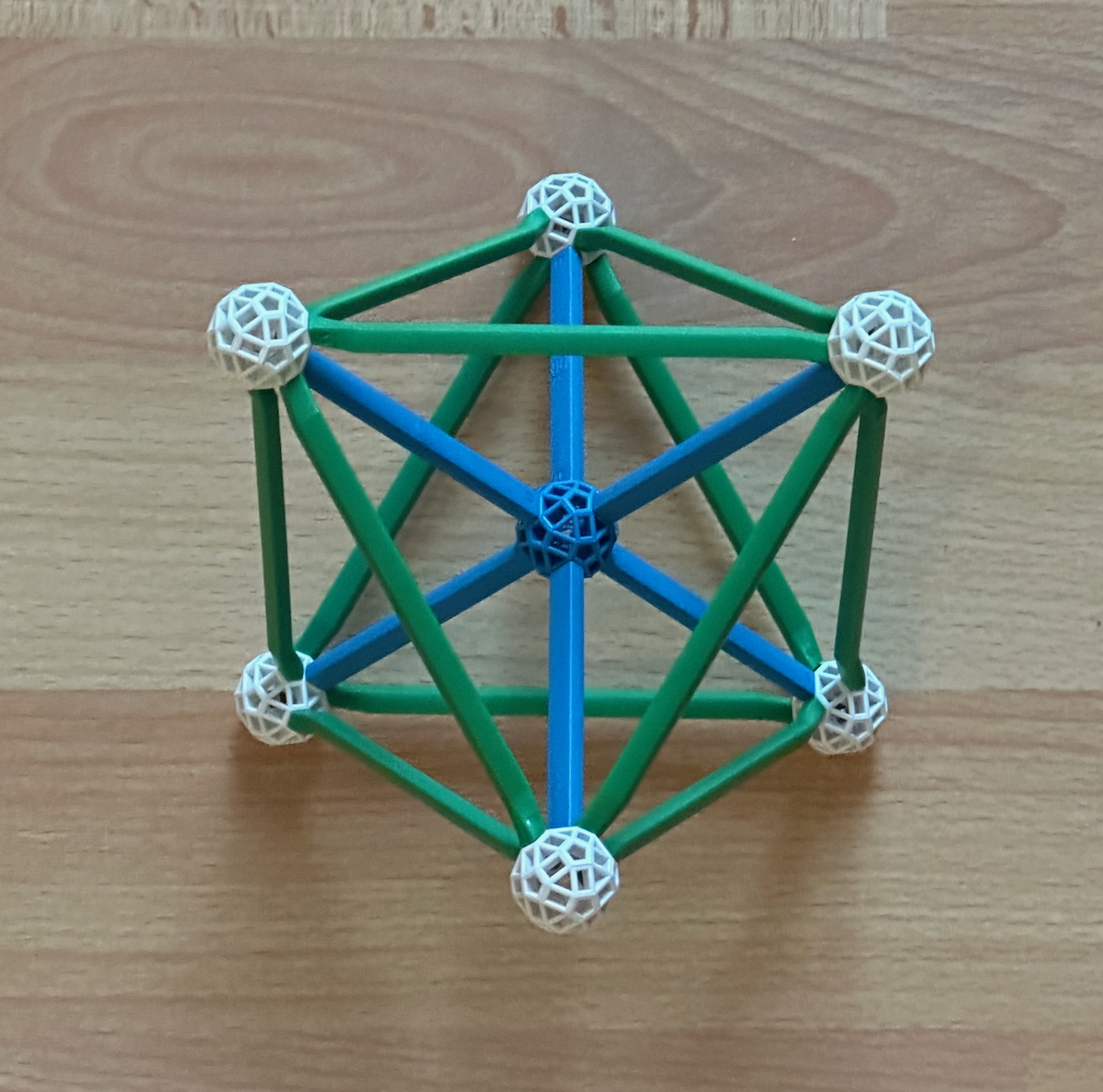

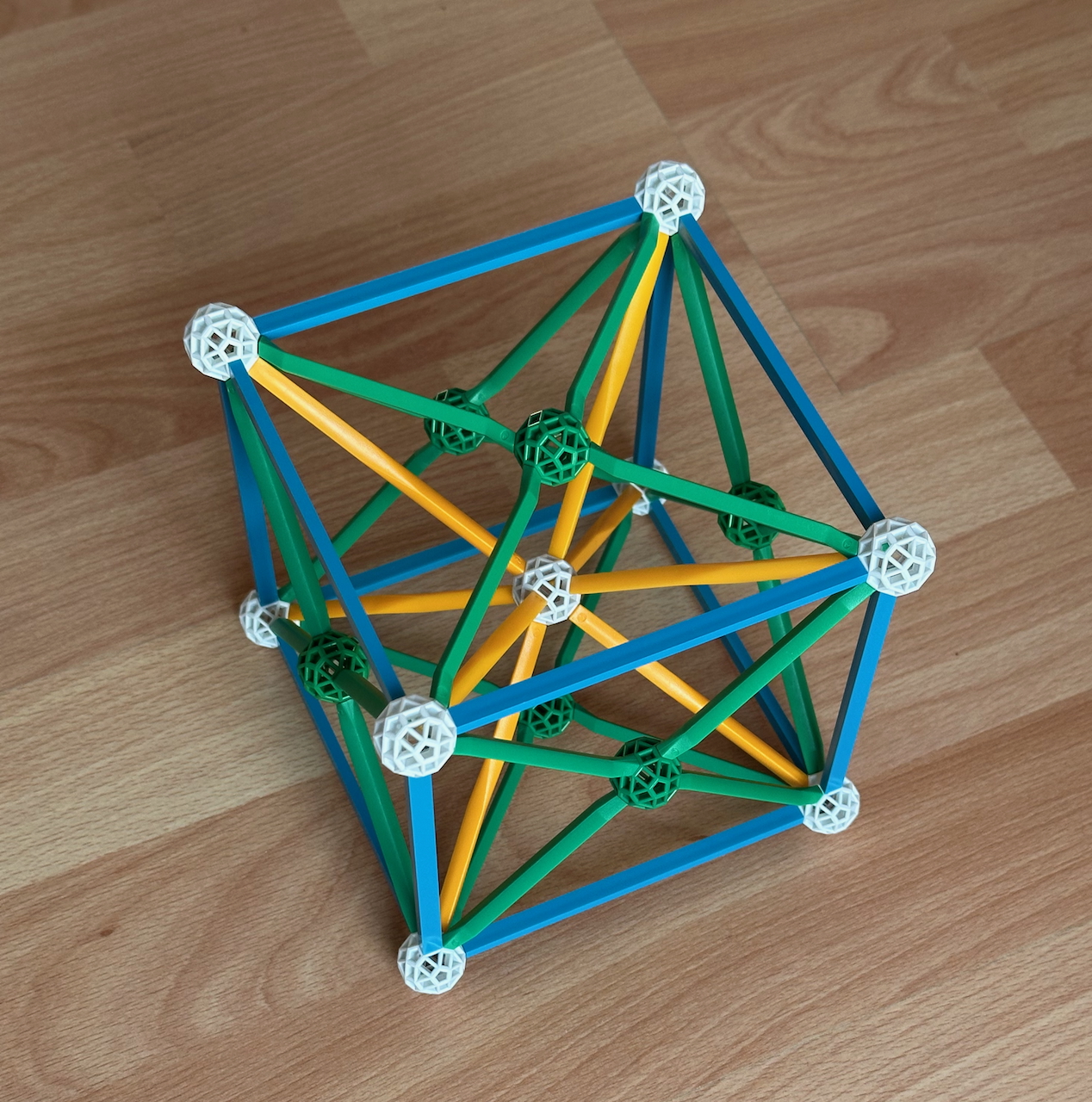

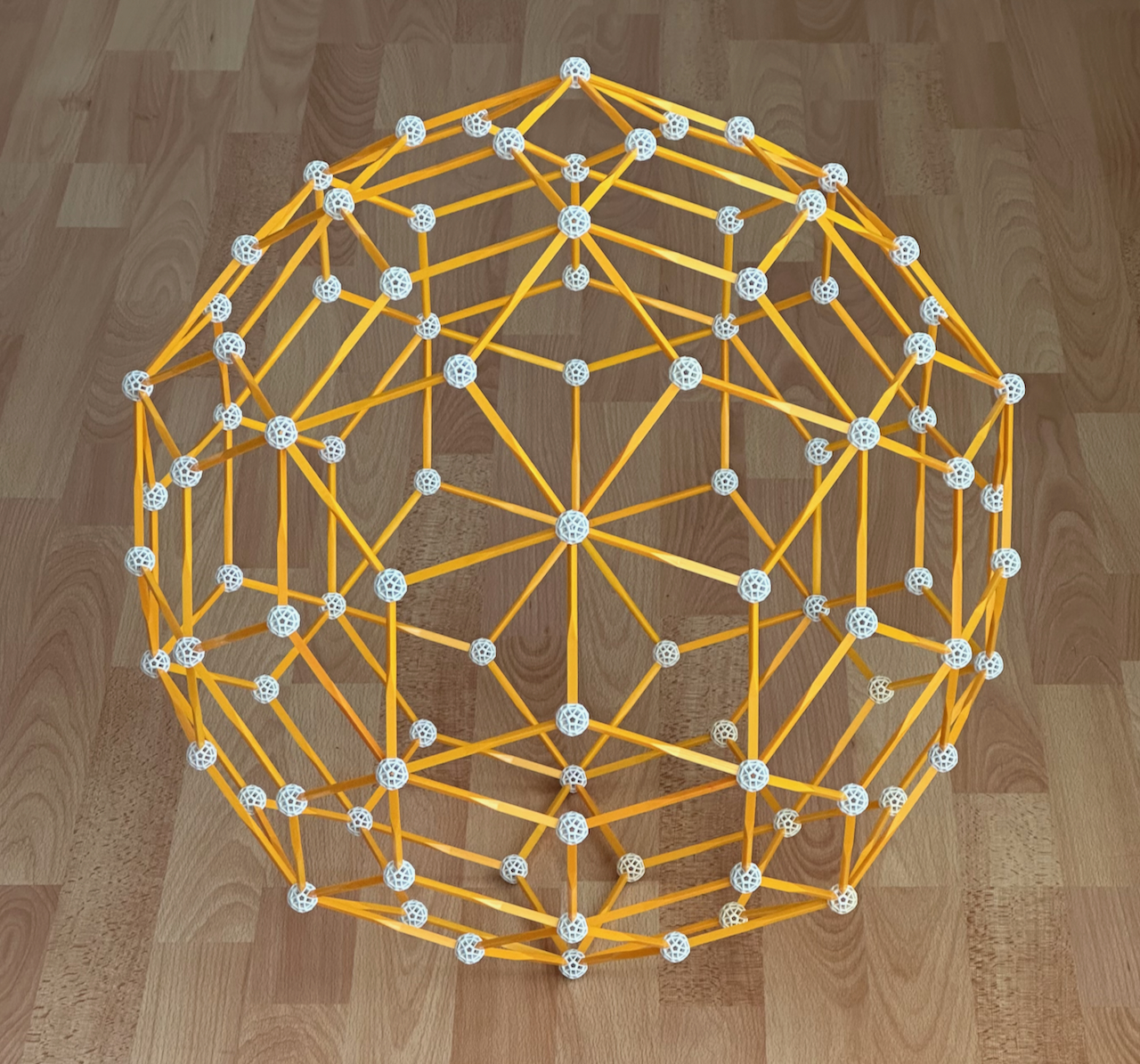

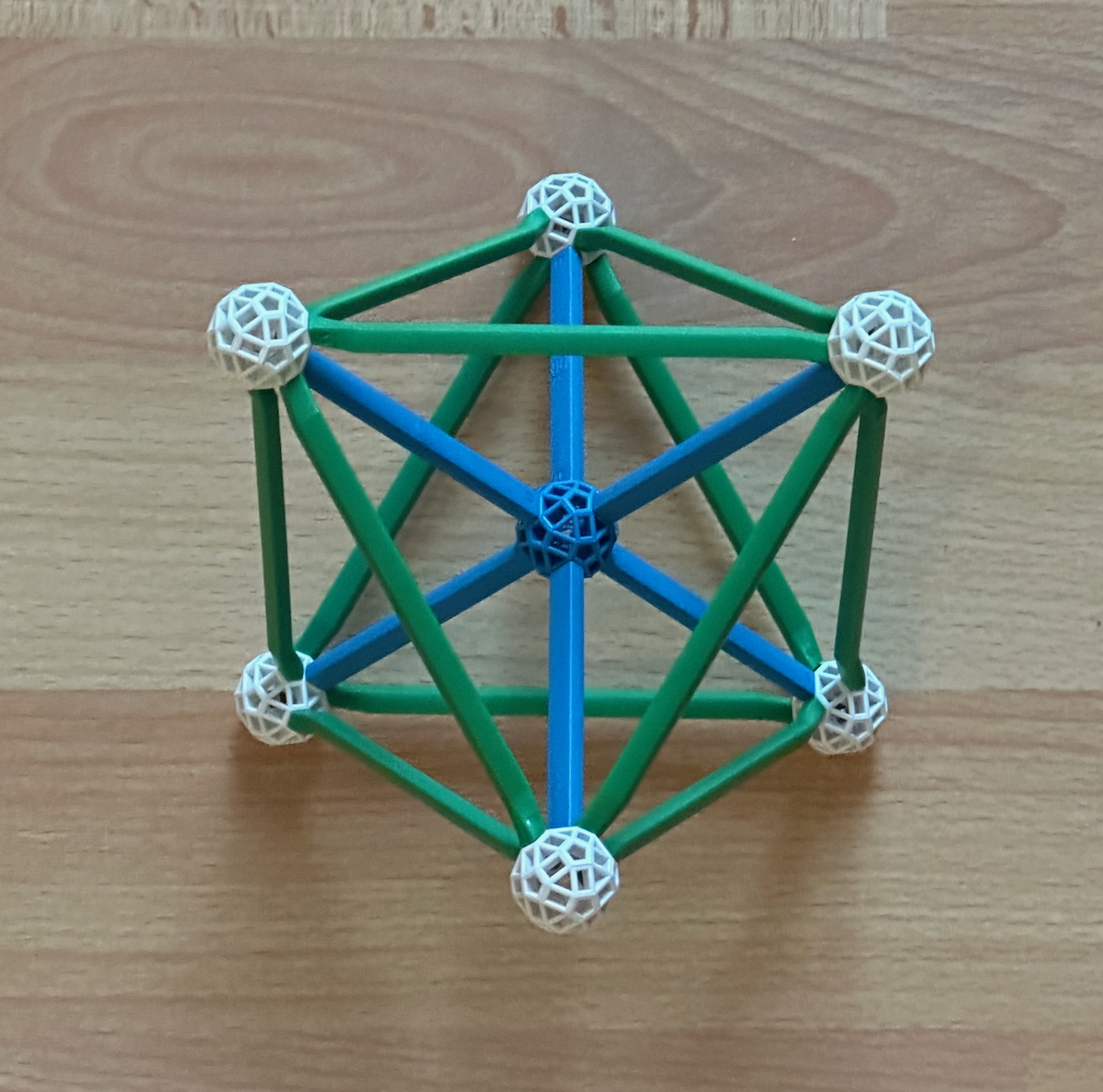

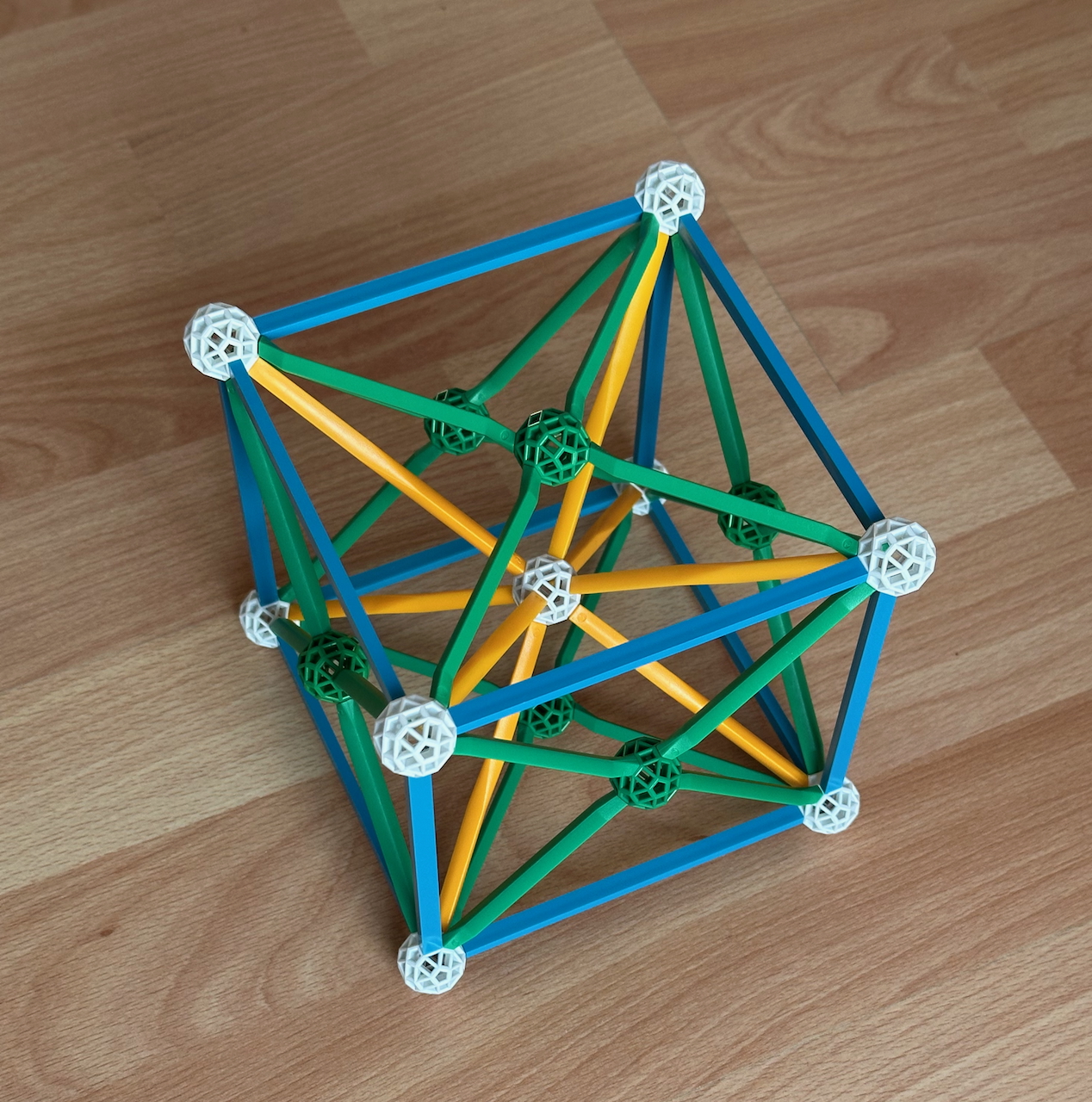

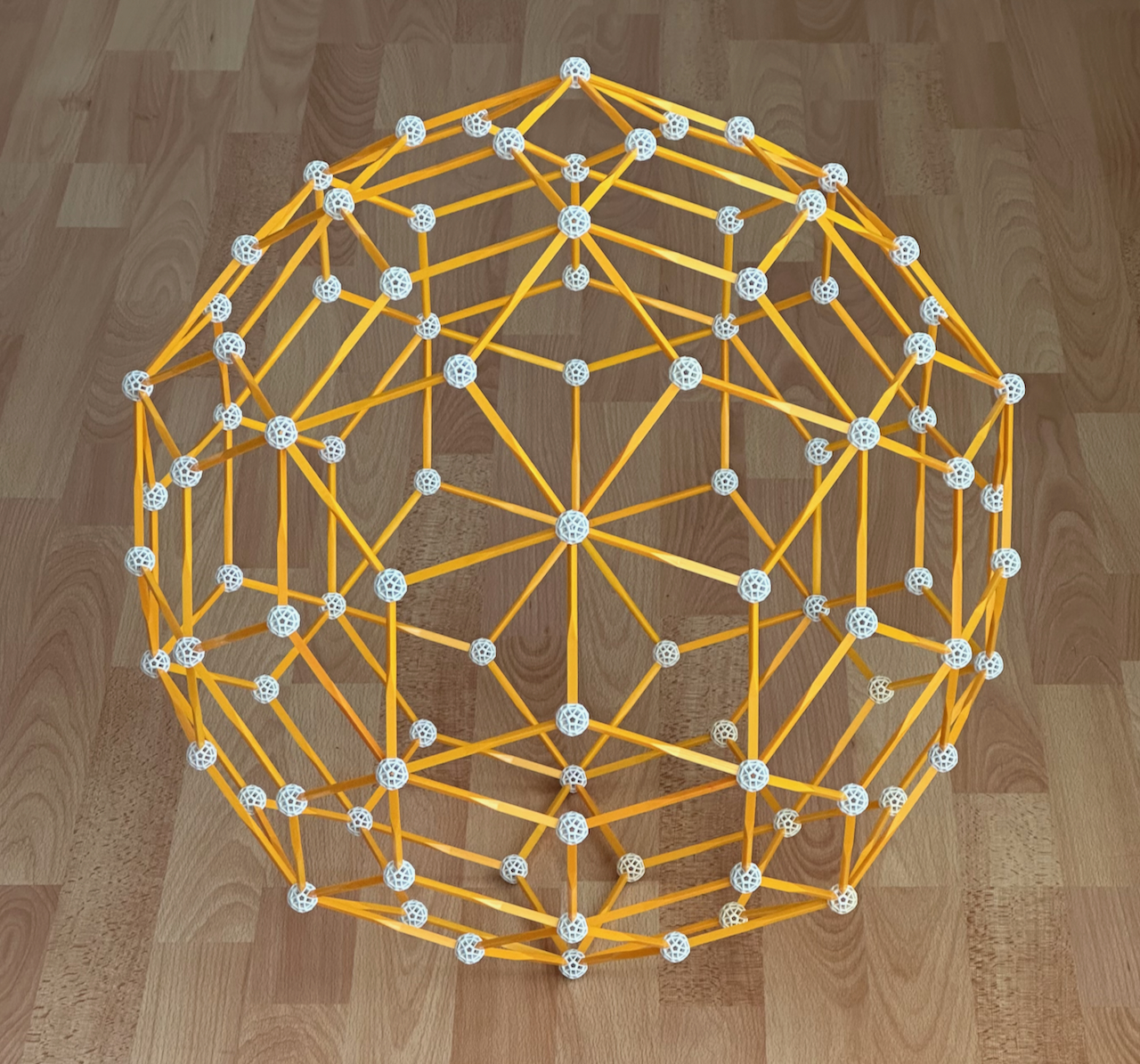

Fig. 10.1: An Octahedral projection of the 5-simplex.

In this model vertices and edges are shown without superposition. All vertices are shown

equally. We can see that, as in all simplices, the edges connect all vertex pairs, and in

this model vertices and edges are shown without superposition. Thus, the model in Fig.

10.1, which is an accurate model of the Octahedral projection of the 5-simplex to three

dimensions, resembles the vertex-first projection of the 16-cell in Fig. 5.4, with the

difference that there are no vertices at the centre.

The 6-simplex has 7

vertices and 7 facets. It is not possible to make an equidistant projection in 3D.

However, using the same projection vector as in Fig. 10.1, its additional vertex will be

placed at the centre of the model. That projection would look identical to that of the

vertex-first projection of the 16-cell in Fig. 5.4. There would be 6 new blue edges

connecting that vertex to all others, which will be superposed on the three blue edges of

the previous model.

The same strategy can be applied to the following equidistant projections of n-simplexes

to make vertex-centered projections of n+1-simplexes.

By the same logic used in the 5-simplex, it is easy to make n equidistant projection for

the 7-simplex, which

has 8 vertices and 8 facets. We can choose the direction of the projection in such a way

that the vertices are distributed as the vertices of a Cube.

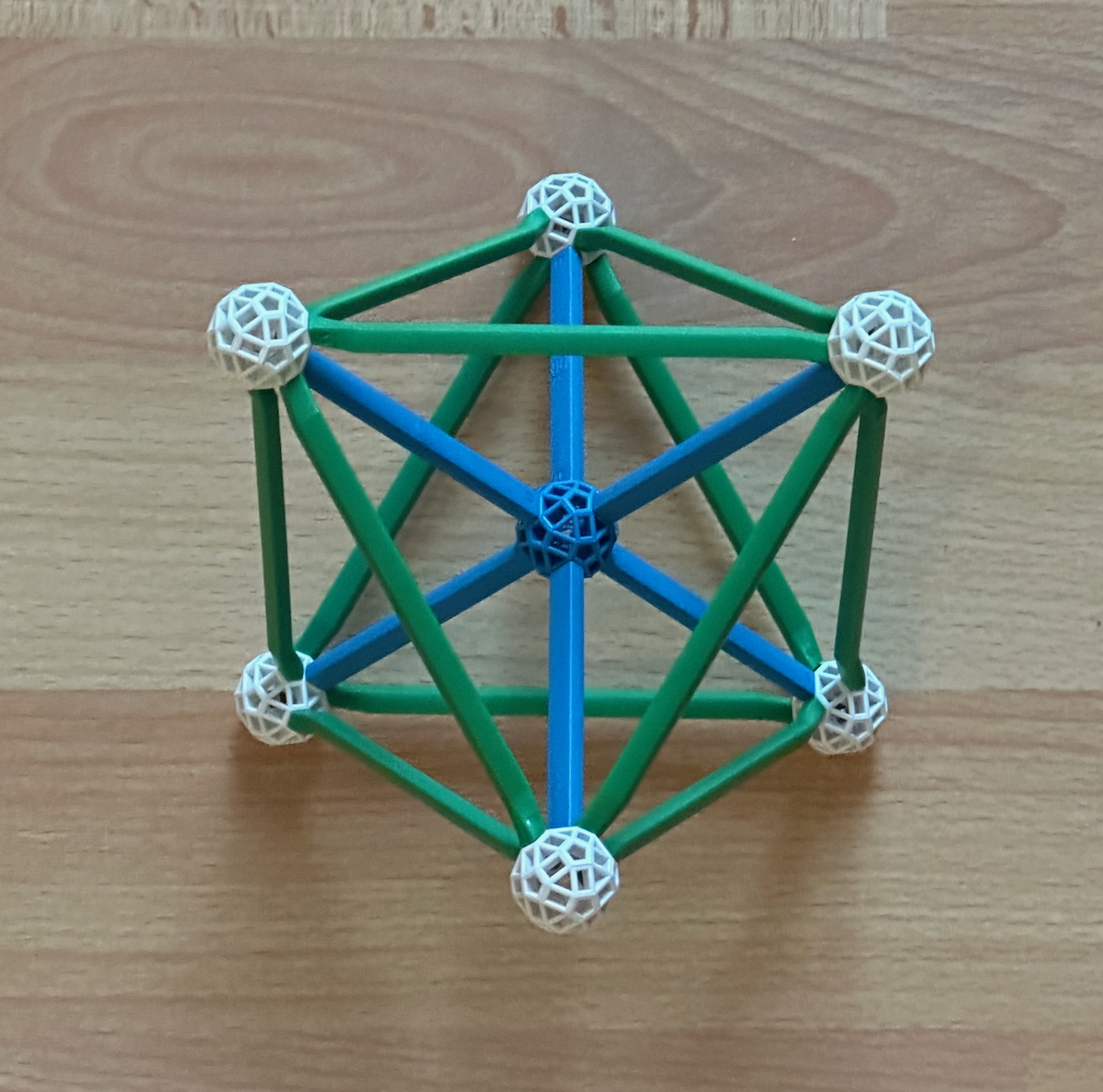

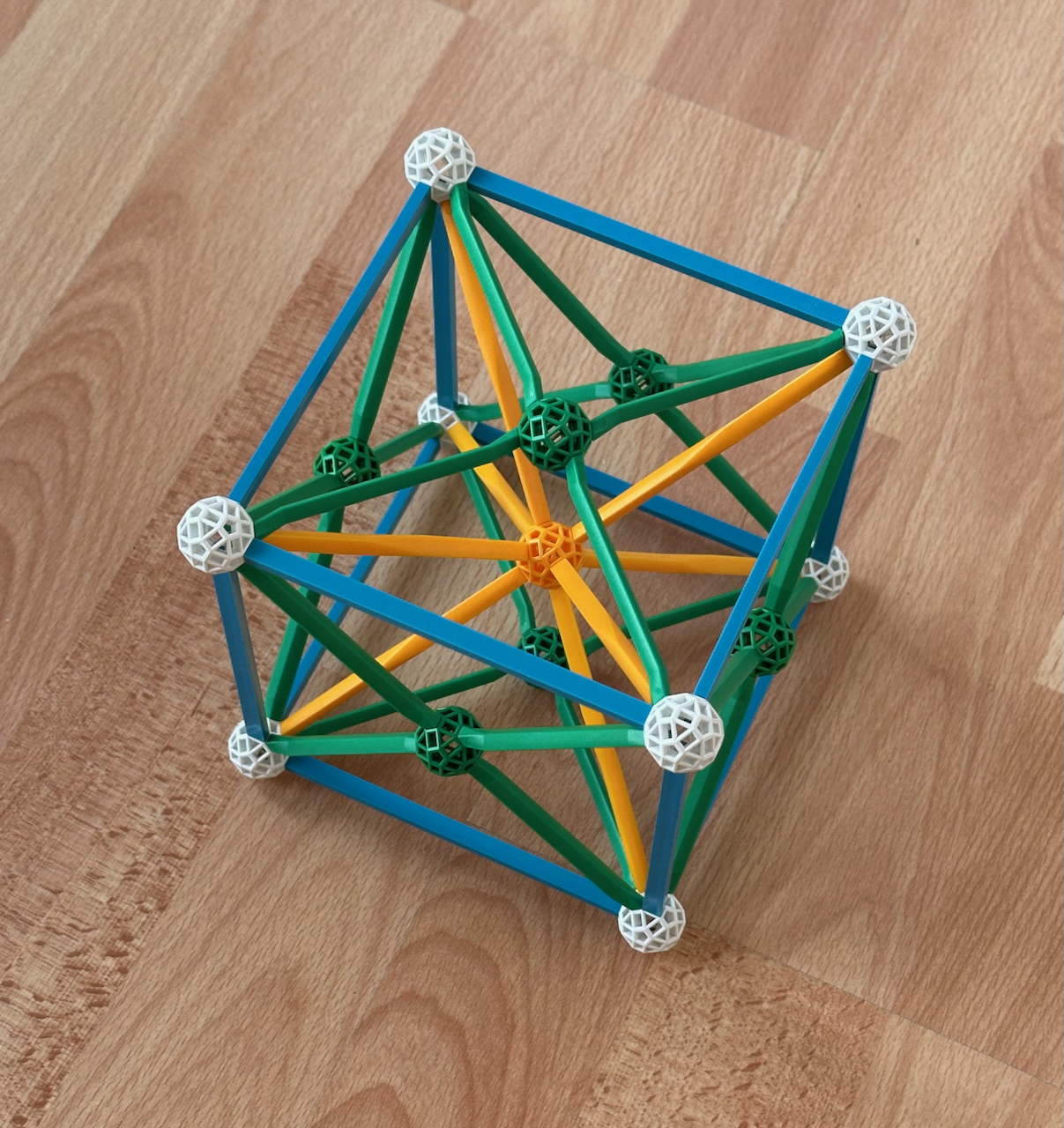

Fig. 10.2: An Octahedral projection of the 7-simplex.

Again, the edges connect all vertex pairs. Thus, the model in Fig. 10.2, which is an

accurate model of the Octahedral projection of the 7-simplex to three dimensions,

resembles the model of the Cube and its faceting in Fig. 4.5b, with the difference that

there are four yellow edges connecting pairs of opposite vertices.

The 11-simplex has 12 vertices and 12 facets. We can choose the direction of the

projection in such a way that the vertices are distributed as the vertices of an

Icosahedron.

Fig. 10.3: An Icosahedral projection of the 11-simplex. This model required 30 B3 struts

and 12 R3 struts, but this can avoided by building the model on a smaller scale, as in

Fig. 4.6c.

Again, the edges connect all vertex pairs. Thus, the model in Fig. 10.3, which is an

accurate model of the Icosahedral projection of the 11-simplex to three dimensions,

resembles the model of the Icosahedron and its facetings in Fig. 4.6c, with the difference

that in Fig. 10.3 there are 6 red edges connecting pairs of opposite vertices.

One could in principle make additional Icosahedral projections of the 19-simplex, for

which the 20 vertices would have the distribution of the vertices of the Dodecahedron and

have 10 yellow edges connecting pairs of opposite vertices, or of the 29-simplex, for

which the 30 vertices would have the distribution of the vertices of the Icosidodecahedron

and would have 15 blue edges connecting pairs of opposite edges. Their models would

resemble, respectively, the models of the Dodecahedron and its facetings (Fig. 4.8) plus

yellow radials and of the Icosidodecahedron and its facetings (Fig. 4.12) plus blue

radials. However, as we'll see below, these projections are not Zomable.

***

The same idea used to make symmetric projections of the simplexes can also be used to make

symmetric orthographic projections of the orthoplexes. The reason is identical to that

used in the simplexes: when we build a n+1 orthoplex from a n-orthoplex, we add, in a line

perpendicular to the n-orthoplex, two new vertices that are equidistant from all its

vertices. This means that, when projecting the n-orthoplex along that perpendicular line,

all vertices must lie at the same distance from the centre, making an equidistant

projection. Projecting the n+1 orthoplex along the same projection vector would add the

two new vertices to the centre of the projection, making a vertex-centred projection.

We now exemplify this. In the cell-centred projection of the 4-orthoplex (the 16-cell, the

lower left of Fig. 5.4), the 8 vertices are arranged symmetrically, which implies they are

arranged as the vertices of a Cube. As remarked then, this projection is especially good

for showing all the vertices separately. This makes it possible to see that the edges -

all shown without superpositions as well - connect all vertex pairs except opposing

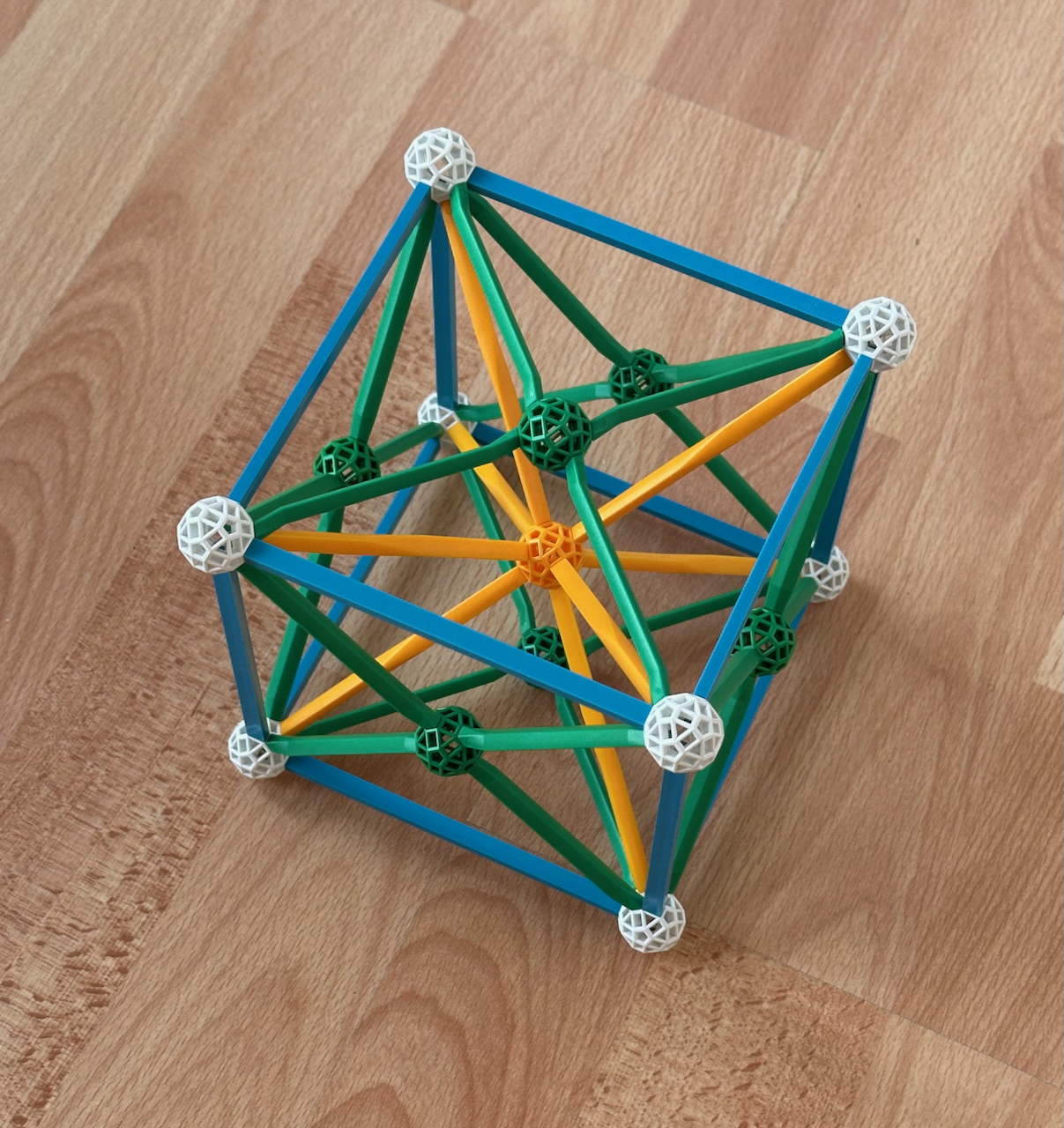

vertices, as in all orthoplexes. From this, we can make a projection of the 5-orthoplex by using the

same projection vector, which adds two new vertices superposed at the centre (see Fig.

10.4). These don't connect to each other, but connect to all others via Y struts. The same

strategy can be applied for making vertex-centred projections of n+1-orthoplexes from

equidistant projections of n-orthoplexes.

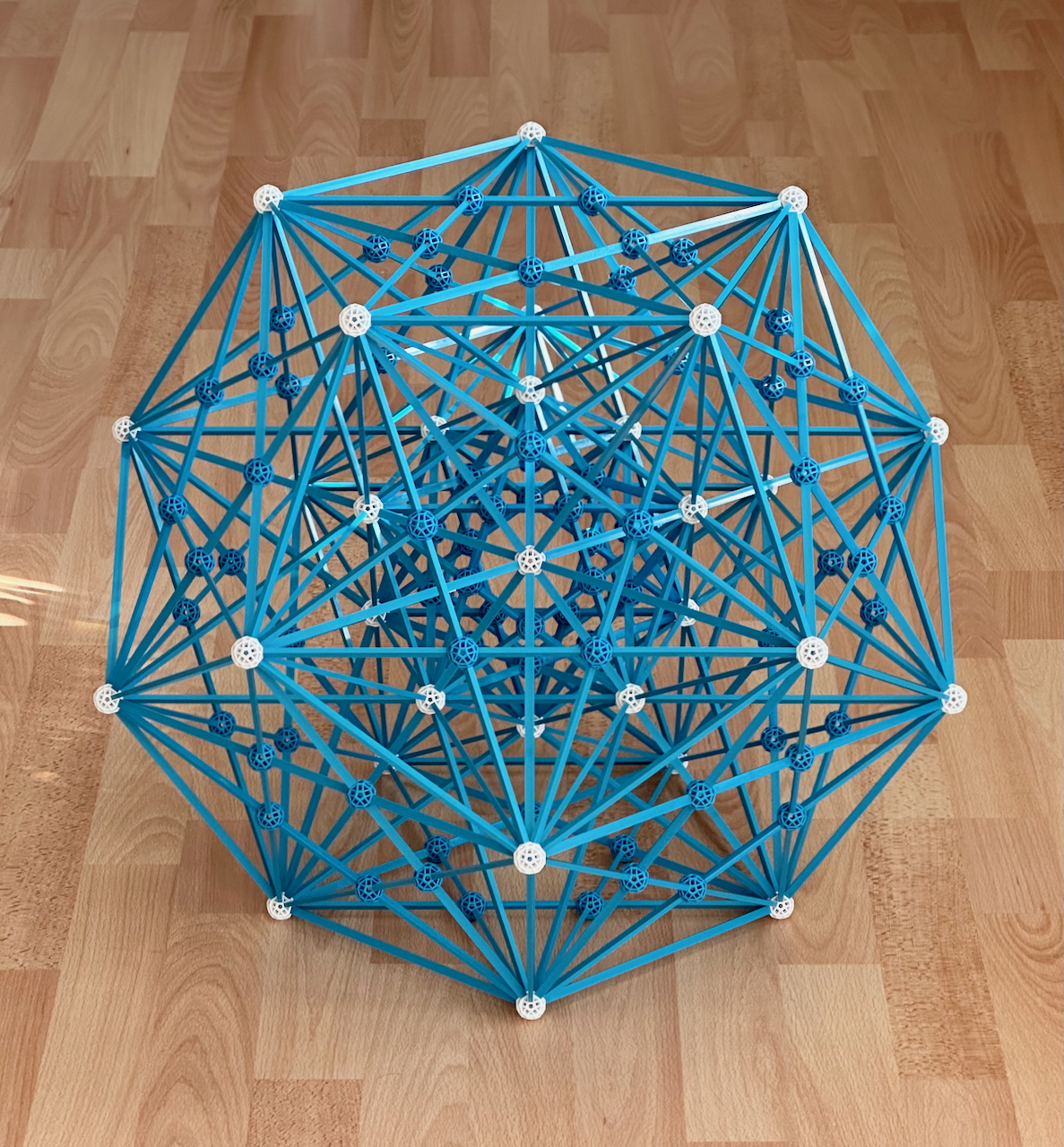

Fig. 10.4: An Octahedral projection of the 5-orthoplex.

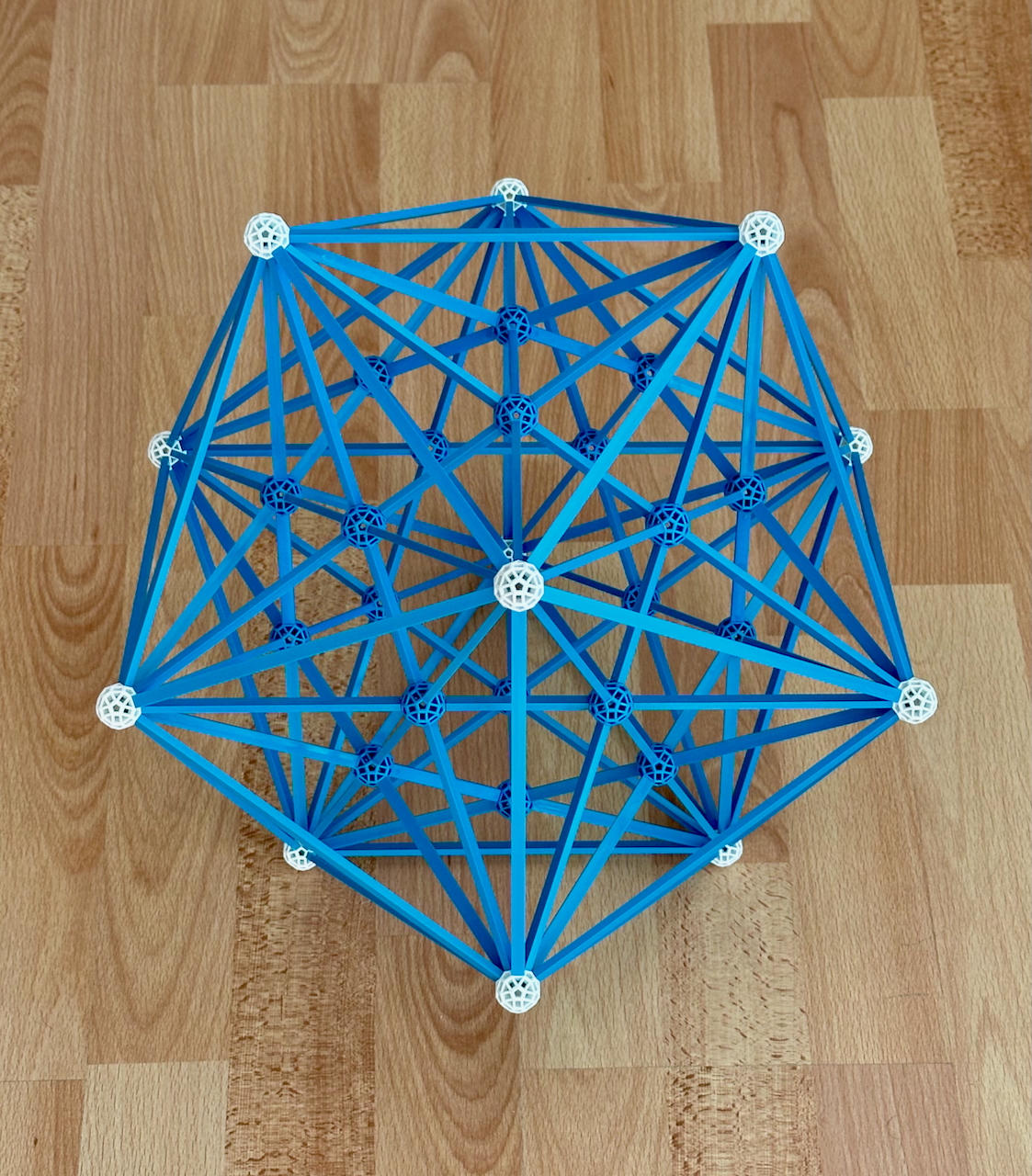

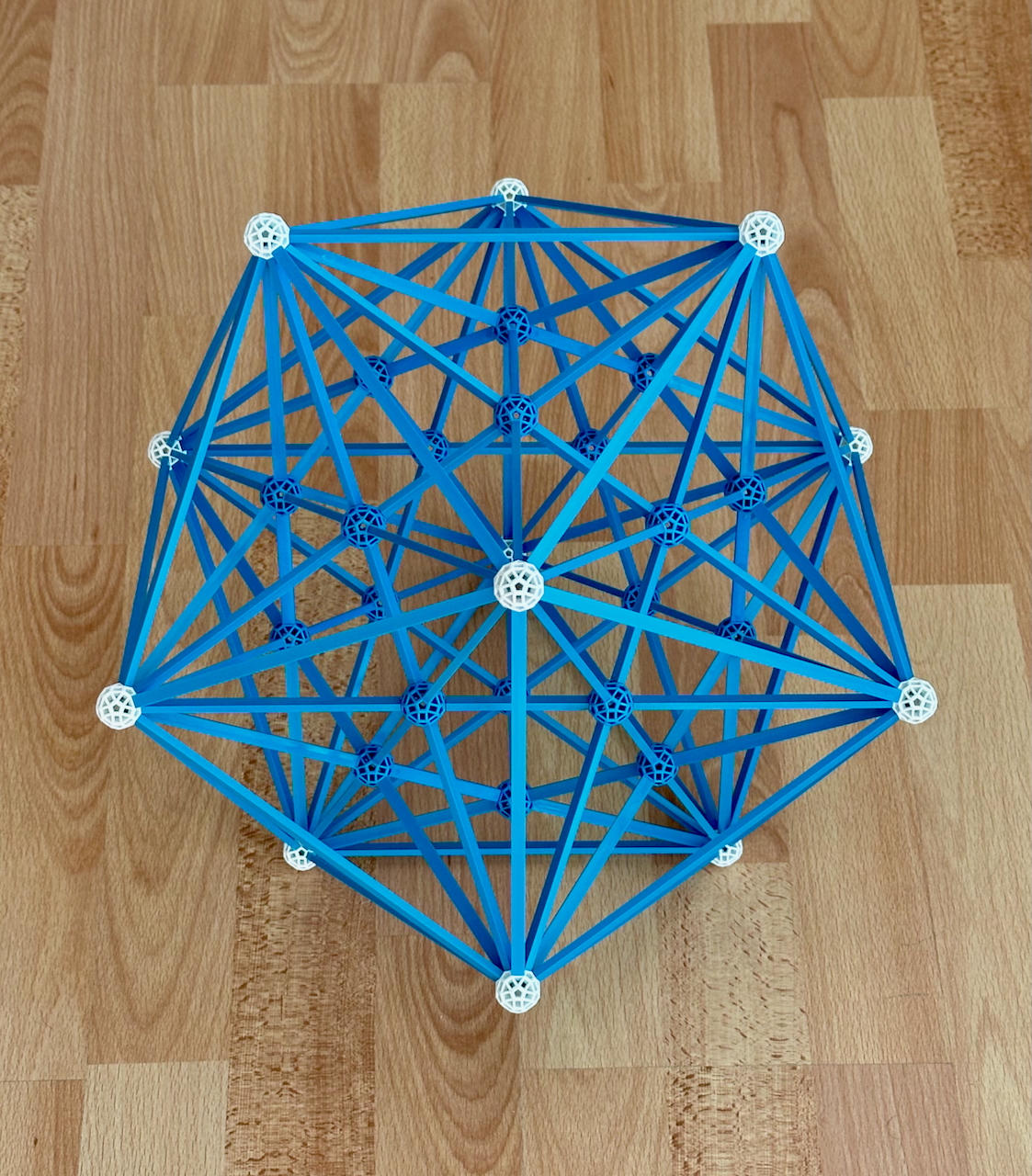

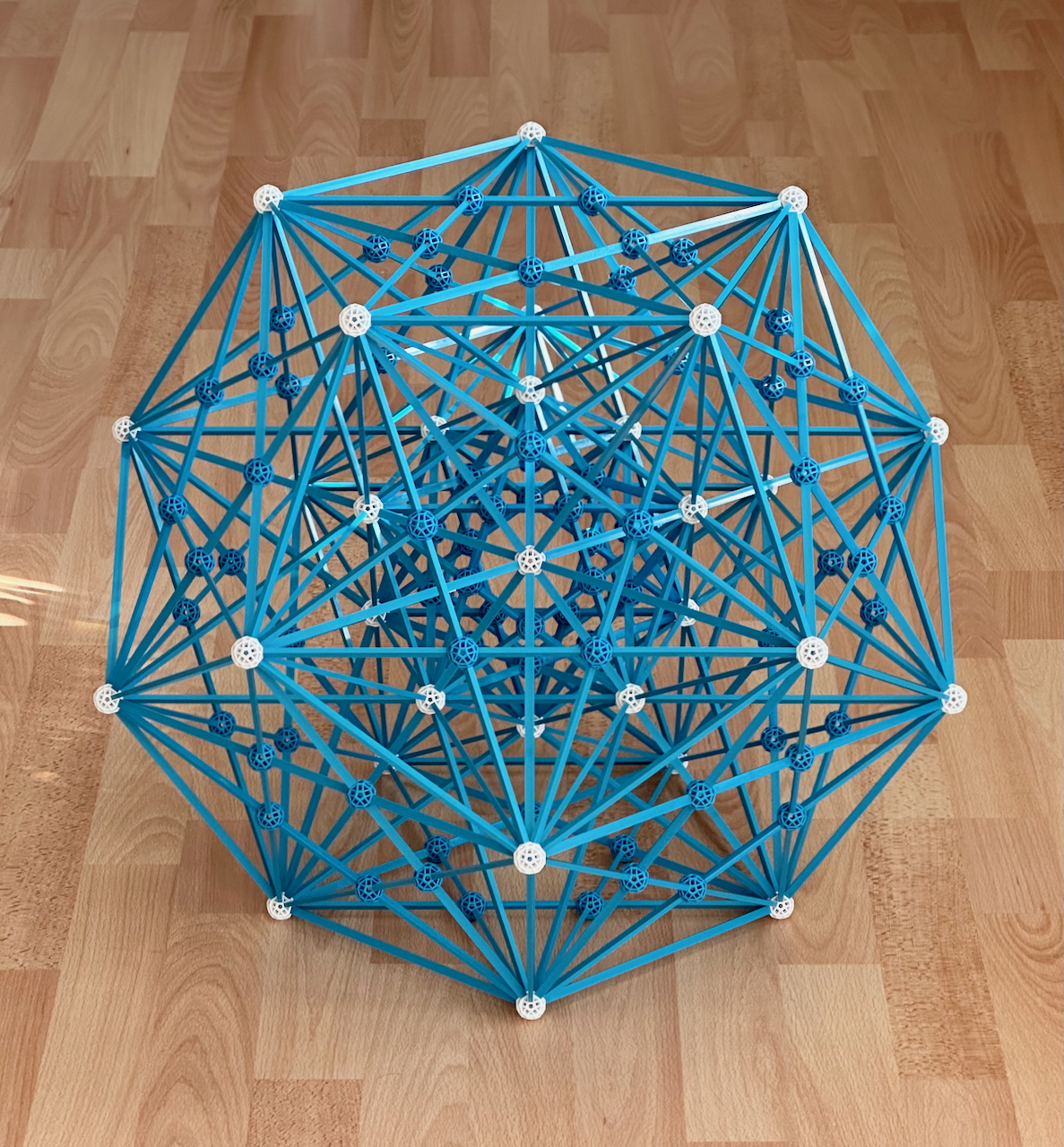

Fig. 10.5 shows the equidistant projection of the 6-orthoplex. In this projection, the

2 × 6 = 12 vertices are arranged symmetrically, i.e., as the vertices of the

Icosahedron. Again, all vertices are shown without superpositions. This allows us to see

that, again, the edges, which are also shown without superpositions, connect all vertex

pairs except opposing vertices. This makes the model different from the model of the

11-simplex in Fig. 10.3, where the red radials were fulfilling that role, but identical to

the model of the Icosahedron and its facetings in Fig. 4.6c.

Fig. 10.5: The Icosahedral projection of the 6-orthoplex. This projection used 30 B3 struts.

This polytope has 60 edges (the 30 of the outer Icosahedron plus the 30 of the inner

Stellated dodecahedron), 160 Triangular faces, 240 Tetrahedral cells, 192 5-cell ridges

and 26 = 64 5-simplex facets.

In the Icosahedral projection of the 10-orthoplex, the 20 vertices will

be distributed as the vertices of a Dodecahedron, and the edges will connect all vertex

pairs except opposing vertices. Thus, the projection will look very similar to the model

of the Dodecahedron and its facetings in Fig. 4.8, with B and G struts, only with the

difference that instead of a Compound of five tetrahedra, a Compound of ten tetrahedra

would be needed, so that all non-opposing vertices are connected. However, as remarked

after Fig. 4.7b, this compound is not Zomable.

The Icosahedral projection of the 15-orthoplex would have its 30 vertices distributed as

the vertices of the Icosidodecahedron. The edges connect all vertex pairs, except opposing

vertices; the resulting projection would look somewhat like the model of the

Icosidodecahedron and its facetings in Fig. 4.12, except that it would require three

additional edge directions that are not Zomable.

***

For hypercubes, the reasoning used above to make the projections no longer applies: when

building a n+1 cube from a n-cube, not all vertices of the n-cube are equidistant from the

new vertices of the n+1 cube. For that reason, the strategy used to make the projections

must be different. The strategy to be adopted is based on the fact that for a n-cube,

there are only n edge directions. Since an orthographic projection is an affine projection

(which preserves parallelism), a projection of a n-cube will also have only n distinct

edge directions.

This implies that several projections of higher-dimensional hypercubes are not only

Zomable, but also Zomable in a single colour, with the models having a high degree of

symmetry. The reason for this can be understood from the study of the models of the Cube

and Tesseract.

The three axes of the Cube can be represented in 3 dimensions without distortion, in three

orthogonal directions, all with blue struts. If we want to project it in two dimensions,

we can choose to project all edge directions equally, in which case they must have a

symmetrical Triangular arrangement (see Fig. 5.2, model B). All edges are represented with

the same length, and all vertices connect to three edges, which represent the full set of

edge directions.

Similarly, for the Tesseract, we cannot represent the four axes as orthogonal directions

in 3-D space, but we can choose to represent them equally, which implies a symmetric

arrangement - in this case the radial struts of a Tetrahedron, all of which are Y struts

(see Fig. 4.3a). This is the vertex-centred projection of the Tesseract in Fig. 5.4. All

edges are represented with the same length, and all vertices connect to four edges, which

have the full set of edge directions.

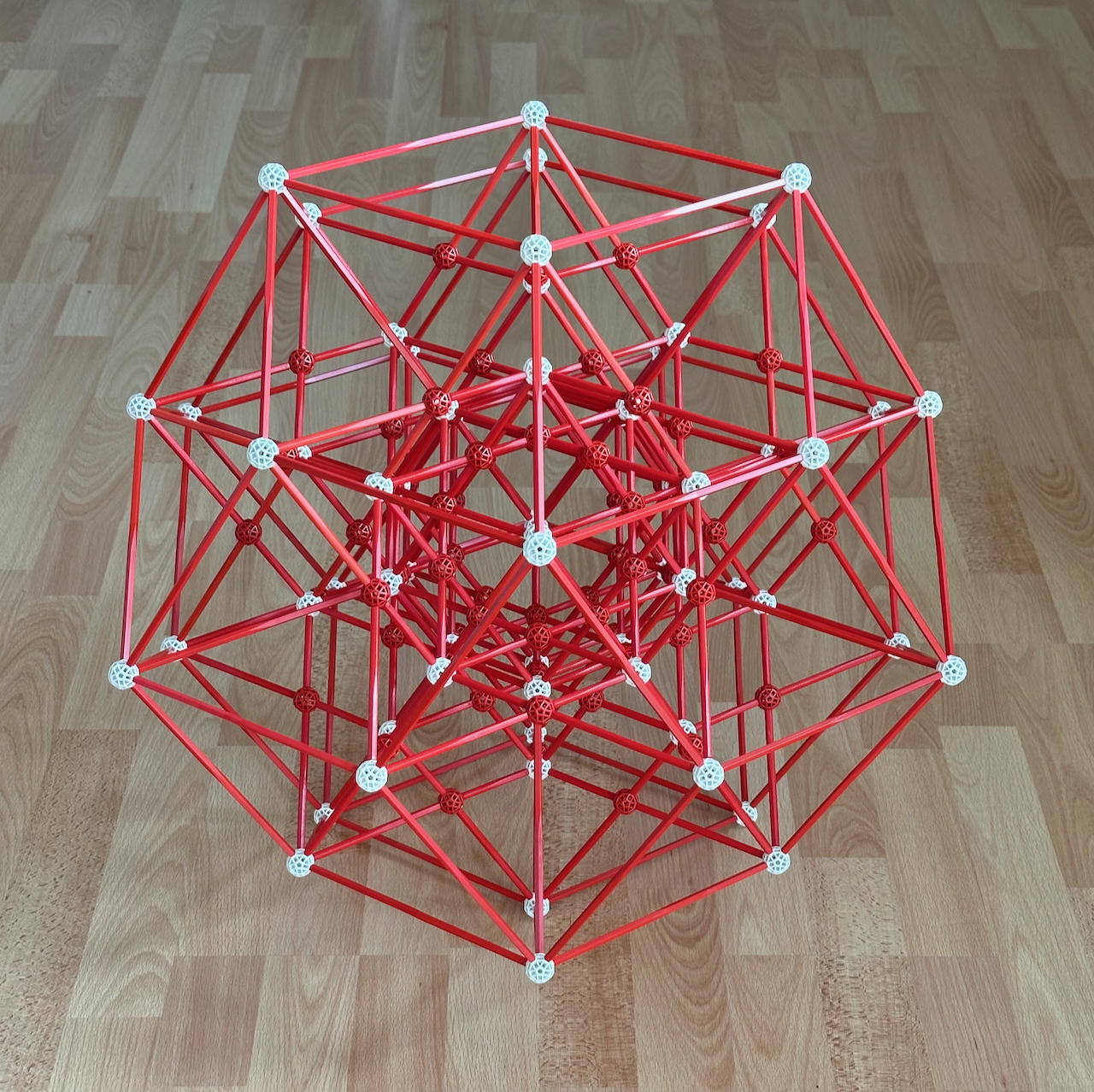

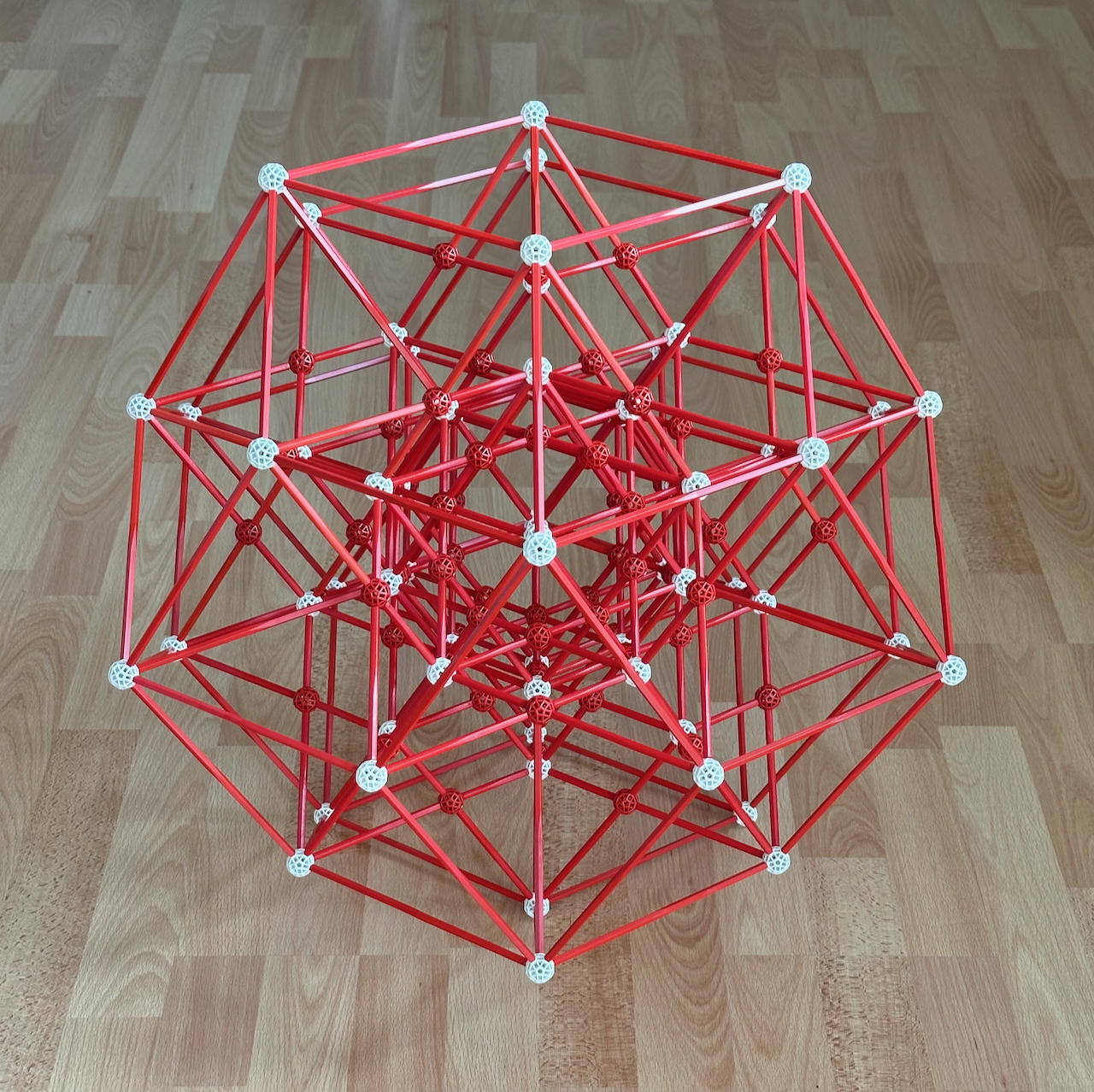

For the 6-cube, we can

also make an orthographic projection to three dimensions and treat all 6 edges directions

equally (implying also symmetrically) by making them parallel the six axes of symmetry of

the Icosahedron, which are represented in the Zometool by the R struts. A model of this

projection is shown in Fig. 10.6. This is the dual of the projection of the 6-orthoplex in

Fig. 10.5. All vertices connect to 6 struts, which represent the full set of edge

directions in the model.

Fig. 10.6: An Icosahedral projection of the 6-cube, the dual of the 6-orthoplex. This is

the dual of the Icosahedral projection of the 6-orthoplex in Fig. 10.5.

I made this model with the help of a vZome model made by Scott Vorthmann. This projection

uses 72 R3 struts. To avoid this, the model can be built on a smaller scale using R00

struts.

All elements are the duals of the elements of the 6-orthoplex in Fig. 10.5. The 12 5-cubic facets correspond to

the the vertices of the 6-orthoplex, like them their projections are all identical and are

associated with the 6 axes of 5-fold symmetry of the projection. The 60 Tesseractic ridges

are perpendicular (in 6 dimensions) to the edges of the 6-orthoplex; the 160 Cubic cells

correspond to the latter's 160 Triangular faces, the 240 Square faces, which are all

projected in the same way (as Golden rhombuses), correspond to its 240 Tetrahedral cells,

the 192 edges are perpendicular to its 192 5-cell ridges and 64 vertices correspond to its

64 5-simplex facets. The arrangement of the 64 vertices is especially beautiful,

corresponding to a doubling of the vertex arrangements of the Icosahedron (12 vertices)

and the Dodecahedron (20). The Golden rhombus projections of the Square faces of the

6-cube are analogous to Yellow rhombus projections of the Square faces in the

vertex-centred projection of the Tesseract (Fig. 5.4).

The fact that both the projections of the 6-orthoplex and 6-cube have a Zomable

Icosahedral projection is no coincidence: both are related to the fact that either the 2

× 6 vertices (of the 6-orthoplex) or the 6 directions of the edges of the 6-cube are

aligned with the 6 axes of 5-fold symmetry of the Icosahedral symmetry. This is a

reflection of the fact that two dual polytopes share the same symmetry, if one of them can

be projected into a lower symmetry, the same happens to its dual.

Note also how much larger the projection is relative to the size of the edge, a phenomenon

we had already see in Figs. 5.2 and 5.4. The reason is counter-intuitive: although the

"side" of a unit n-cube is always 1, the distance to the center (√n/2) increases

without bound with n. However, unlike those projections, this is not a vertex-centred

projection. In this model, we start to see that projecting objects from dimensions higher

than four into three dimensional space leads to a concentration of vertices and edges near

the centre.

Fig. 10.6a: The Great rhombic triacontahedron.

To build the model in Fig. 10.6, we start by building a core with the vertices and edges

of the Great Rhombic

triacontahedron (Fig. 10.6a). Perhaps this is the reason why this pair of polytopes

appears in the cover of Coxeter's ``Regular Polytopes".

Any orthographic projection of a hypercubic element into a plane will be circumscribed by

a polygon with central symmetry, where, as in the original hypercube, each edge has an

opposite edge that is parallel to it. Any orthographic projection of any n-cube to 3-D

space will therefore be bound by a polyhedron with this type of faces: the aforementioned

zonohedra. The

characteristics of their faces imply that all faces are part of face rings, each

containing a particular edge direction that does not exist outside that ring, each of

these corresponds to one of the directions of the edges of the hypercube.

In the case of the projection in Fig. 10.6., the envelope is a zonohedron with Icosahedral

symmetry that is constructible with R struts and has Golden rhombic faces, which are

projections of Square faces. We have seen this object before, it is the Rhombic

triacontahedron. This situation is analogous to the envelope of the vertex-first

projection of the Tesseract in Fig. 5.4, a Zonohedron with Octahedral symmetry and Yellow

rhombic faces (also projections of Square faces) that can be represented with Y struts,

the Rhombic dodecahedron. Just as the vertex-first projection of the Tesseract showed the

parallelism between the yellow radials of the Cube (Fig. 4.3a) and yellow edges of the

Rhombic dodecahedron, the model in Fig. 10.6 shows the parallelism between the red radial

edge directions of the Icosahedron (Fig. 4.2) and the red edges of the Rhombic

triacontahedron.

Fig. 10.7: My Big Ball of Whacks (6-color edition), with each colour showing five of the

ten faces in each equatorial ring. Each colour is associated with a single edge direction,

which is perpendicular to that ring.

There is a magnetic toy puzzle that can be arranged as a Rhombic triacontahedron, the Big

ball of whacks. The pieces come in six colours. At first I was wondering why six: with

five colours, it would have been easier to create symmetrical patterns. However, I could

find a pattern where the five Golden rhombuses of each of the six colours covers half the

faces of a particular equatorial ring of 10 faces (each of the 30 faces belongs to two

rings). For each of these colours/rings there is a single edge direction that is common to

all the faces in the same ring, and perpendicular to the ring itself (see Fig. 10.7); this

edge direction is absent outside this ring. This is a very nice general illustration of

the concept of a Zonohedron, and in this case of the 6 edge directions of the projection

of the 6-cube in Fig. 10.6.

The same logic can be applied to projections of some higher-cubes. An an example, if

during an orthographic projection to 3-D space we treat all 10 edge directions of the 10-cube equally and

therefore symmetrically, we must make them parallel to the 10 axes of 3-fold symmetry of

the Dodecahedron. Since these are represented in the Zometool by Y struts (see Fig. 4.3c),

this results in a yellow

projection of the 10-cube with full icosahedral symmetry. This is the dual of the

aforementioned Dodecahedral projection of the 10-orthoplex. This projection is so complex

that it is impractical to make a physical model of it with the Zometool. However, its

envelope is simple: it is the largest Zomable yellow zonohedron, the rhombic enneacontahedron

(see Fig. 10.8). This has 10 edge directions, and thus 10 face rings, 5 yellow rhombuses

around each of the 12 vertices in the 6 axes of 5-fold symmetry, and 30 long yellow

rhombuses centred on the axes of 2-fold symmetry. These rhombuses are projections of

Square faces.

Fig. 10.8: The Rhombic enneacontahedron. This zonohedron is the envelope of the Icosahedral

projection of the 10-cube.

If, in an orthographic projection of the 15-cube to 3 dimensions we treat all its 15 edge

directions equally, we must make them parallel to the 15 axes of 2-fold Icosahedral

symmetry, resulting in a blue projection of the 15-cube with full icosahedral symmetry.

This would be the dual of the aforementioned Icosidodecahedral projection of the

15-orthoplex. Its envelope is the largest blue zonohedron that can be represented with the

Zometool, the Truncated

icosidodecahedron.

This logic continues for higher dimensions: we can still make symmetrical models, but now

we can no longer treat all edge directions equally. Given that the Zometool connector has

31 axes of symmetry (6 red, 10 yellow and 15 blue), it can theoretically represent an

Icosahedral projection of a 31-cube. While that projection itself is practically

impossible to make, its zonohedral envelope is relatively simple.

Finally, we should also remark that a simple Cube (n = 3) also represents projections of

all n-cubes with n > 3, where all other dimensions are reduced to points (an example of

this is the cell-first projection of the Tesseract in Fig. 5.4). The same applies to all

other models of n-cubes in this site.

Semi-regular polytopes

As we remarked when discussing the partially regular polychora, associated with the

orthoplexes are the non-convex demicrosses. The facets of the

n-demicross are half of the 2n n−1-simplex facets of the n-orthoplex plus

its n equatorial n−1-orthoplexes; the vertex figure is the n−1-demicross; all

other elements are as in the n-orthoplexes. This works because, as mentioned above, the

vertex figures of the n−1-simplices and orthoplexes are, respectively,

n−2-simplices and orthoplexes. The identical vertex and edge arrangements imply that

all Zometool projections of n-orthoplexes in this site also depict n-demicrosses. The

demicrosses have a special characteristic of being non-orientable.

There is a related infinite family of convex uniform polytopes, the aforementioned demicubes. The

demicrosses are obtained by removing alternate facets of orthoplexes; the demicubes are

convex polytopes obtained by removing alternate vertices of the duals of the orthoplexes,

the hypercubes. This implies that the demicrosses share the symmetries of the demicubes.

The operation of removing half of the vertices of a n-cube to form a n-demicube forms an

equal number (2n−1) of n−1-simplices under the removed vertices,

the reason is that they are the vertex figures of the n-cube; this can be visualised

easily in the case of the formation of a Tetrahedron from a Cube. The subtraction of

alternated vertices from the 2n n−1-cubic facets transforms them into 2n

n−1-demicubic facets. The number of n−1 simplices and their arrangement is the

same in a n-demicube and n-demicross. The number of n−1-demicubic facets in the

n-demicube is twice the number of n−1-orthoplex facets in the demicross because the

latter are ``equatorial'' facets.

A consequence of the formation of the demicubes from hypercubes is that we can do the same

for the hypercubes from a hypercubic honeycomb to form

a demicubic

honeycomb, in which the facets are demicubes and (centered on the deleted vertices)

orthoplexes. Therefore, in general, these honeycombs are not regular.

The demi-hypercubic family is thus far hidden because, as we've seen here, all uniform polyhedra and polychora that have their

symmetries already exist as members of other families, two of them being regular: the

demi-Cube is the Tetrahedron (where the demi-cubic facets are 2-sided "polygons", the

edges of the Tetrahedron, in this case we only see the 2-simplex faces) and the

demi-Tesseract is the 16-cell - this is regular because both the 3-demicube and the

3-simplex facets are identical (Tetrahedra). The same happens to the demicubic honeycombs:

In 3 dimensions, this is the Tetrahedral-

Octahedral honeycomb; in 4 dimensions it coincides with the 16-cell honeycomb: this is

regular because the 16-cell is both a demicube and an orthoplex.

It is only in 5 dimensions that we find new polytopes that

have the demi-hypercubic symmetry as their highest symmetry. Of special interest is

the 5-demicube, which

has 10 16-cells and 16 5-cells as facets; this makes it semi-regular. But, despite the

fact that this family is infinite, the list of demicubes that are either regular or

semi-regular ends here! Interestingly, all n-demicrosses (which have the same symmetry)

are not only semi-regular, with n−1 simplices and orthoplexes as facets, but also

(as defined in this site) partially regular: a semiregular faceting of a regular polytope.

The next member of the family is the uniform 6-demicube. Like the 6-orthoplex and

6-cube, this has a beautiful Icosahedral projection (see Fig. 10.9).

Fig. 10.9: One of the two Icosahedral projections of the 6-demicube.

The projection cannot be represented on a smaller scale, because it uses B0 struts. The

model requires the use of 90 B3 struts.

In the formation of a n-demicube from a n-cube, all m-cubic (with 1 < m < n) elements

become m-demicubes. Thus, in the case of of the transformation of the 6-cube into a

6-demicube, the 12 5-cube facets of the former are replaced by 12 5-demicubes, its 60

Tesseract ridges are replaced by 60 16-cells, its Cubic cells are replaced by Tetrahedral

cells and the 240 Square faces become 2-demicubes, which as mentioned in the case of the

Tetrahedron are 2-sided polygons - the full set of 240 edges of the 6-demicube. These are

one set of diagonals of the Square faces of the 6-cube. The 6-demicube has 32 vertices,

half of those of the 6-cube. Under the 32 vertices of the 6-cube that disappeared, 32 new

5-simplex facets appeared, which are the vertex figures of the 6-cube. These have 32

× 6 = 192 5-cell ridges, as many as the edges of the 6-cube; the 5-cell is the edge

figure of the 6-cube. The vertex figure is the Rectified

5-simplex.

We now discuss edge models of demicubes. In Fig. 4.5b, on the right, we see how the

transformation of a Cube into a demicube (Tetrahedron) depends on the choice of vertices

we "delete", i.e., of how we bisect the Square faces of the Cube. In Fig. 5.4, both

projections of the 16-cell result from bisecting the Square faces of the vertex-first

projection of the Tesseract, which are projected as Yellow rhombuses. If for the outer

rhombuses we choose the longer diagonals (G struts, see Fig. 4.9) and for the others the

shorter diagonals (B struts), we obtain the vertex-centred projection of the 16-cell;

which has an Octahedral envelope. If for the outer rhombuses we choose the shorter

diagonals (B struts), and for the others the longer diagonals (G struts), we obtain the

cell-first projection of the 16-cell, which has a Cubic envelope.

To make Icosahedral projections of the 6-demicube with the Zometool, we start from the

Icosahedral projection of the 6-cube in Fig. 10.6 and bisect all Square faces, all of

which are projected in that model as Golden rhombuses. As seen in Fig. 4.9 both diagonals

of a Golden rhombus can be represented by B struts; for that reason, the two Icosahedral

projections of 6-demicubes will be entirely represented by B struts. If, for the outer

Rhombic faces we choose the smaller diagonals, we obtain the projection in Fig. 10.9,

which has a Dodecahedral envelope. If we choose the longer diagonals, we obtain a second

projection with an Icosahedral envelope. Interestingly, both projections would look

exactly the same when seen from a 5-fold symmetry axis!

The projection in Fig. 10.9 is notable for having the edges of all stellations of the

Dodecahedron (Fig. 4.6b) and of its facetings in Fig. 4.8, with the exception of the

Compound of five tetrahedra.

***

To proceed, we will need to discuss the properties of some of the higher-dimensional

symmetry groups. For the linear CD graphs of the Simplexes, Hypercubes and Orthoplexes,

ringing a single node at either end generates a regular polytope. As we've seen for the

3-branch graph of the 4-D demicubic symmetry, ringing any single node creates a regular

polychoron, either a 16-cell or, in the case of the central node, a 24-cell. However, for

other 3-branch graphs this is generally not the case, as discussed below, even though

their Wythoff constructions are identical to those of the regular polytopes.

For such "Wythoff-regular" polytopes, Coxeter introduced a handy, compact notation. This

consists of three numbers, which are the lengths of the branches of the CD graph, none of

which counts the central node. The sum of their lengths must therefore be the dimension of

the polytope − 1 (which accounts for that central node). The first number designates

the length of the branch for which the end node is being ringed. The lengths of the other

two branches are indicated in subscript. For polytope kij, the facets are

k(i−1)j and ki(j−1) polytopes and the vertex figure is a

(k−1)ij polytope.

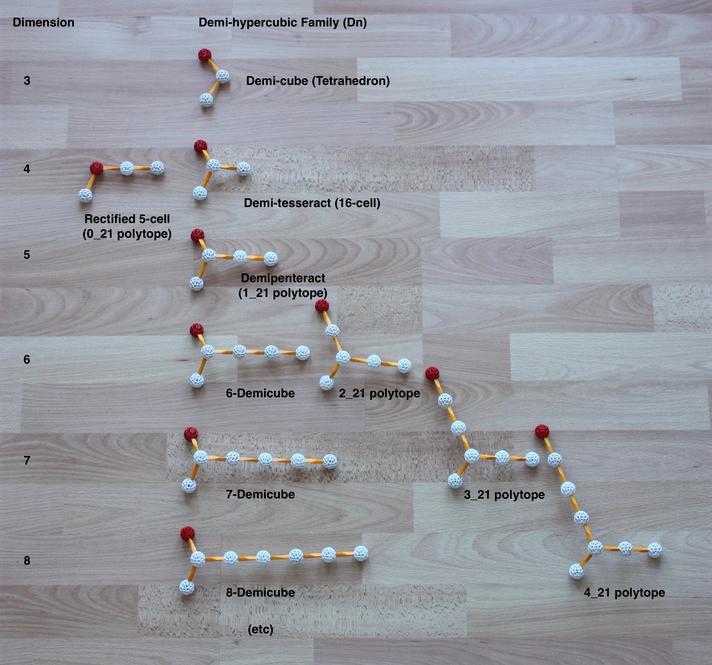

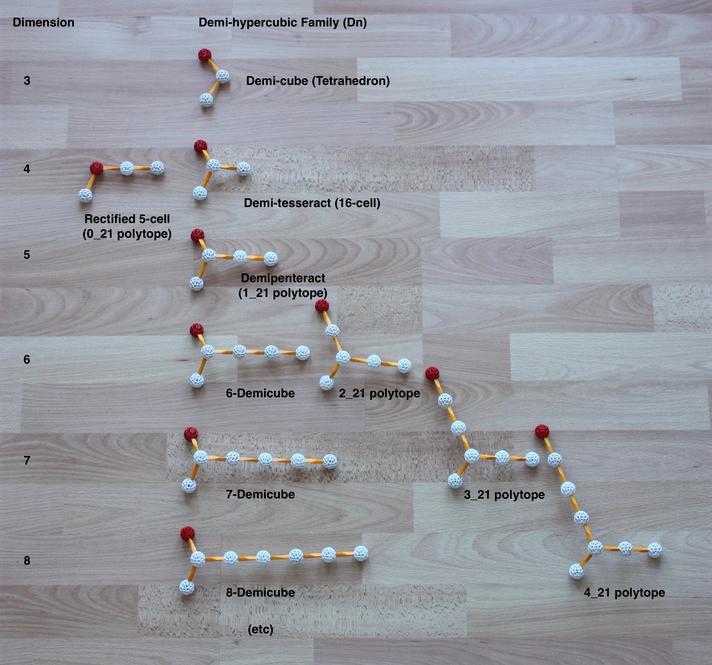

The CD graphs of the demicubic symmetries can be seen arranged in a column in Fig. 10.10.

They always have two branches of length one and a branch of arbitrary length. The

demicubes result from ringing the node at one of the branches of length one (in black) -

they are therefore, in Coxeter's notation, 1k1 polytopes. Their facets are

either 1(k−1)1 polytopes - the n−1-demicubes - or 1k0

polytopes, which are linear chains ringed at one end, the simplexes.

Fig. 10.10: The CD graphs for the demicubes (vertical column), rectified 5-cell (left)

and three higher-dimensional semi-regular polytopes (right). The nodes being ringed are

indicated by the red balls.

However, something interesting happens when we ring the last node of the long branch. This

produces a k11 polytope that has only simplex (k10) facets. Also, as

we see by cutting one node from the k-branch, this polytope has (k−1)11

polytopes as vertex figures. From their structure in 3 and 4 dimensions, we find they are

orthoplexes. Thus, as for 3 and 4 dimensions, the demicubic symmetries can always generate

the orthoplexes.

***

The semi-regularity of the 5-demicube marks it as a member of a family of semi-regular

convex polytopes with the same behaviour of the demicrosses, the k21 polytope

family. Their CD graphs are also shown in Fig. 10.10 in a descending diagonal. As in

the case of the orthoplexes above, the fact that in this family the node being ringed is

the variable integer (k) implies that the k21 polytope is the vertex figure of

the (k+1)21 polytope. That it is semi-regular can be seen by subtracting nodes

from the other two branches: this produces k20 polytopes (simplexes) and

k11 polytopes, the orthoplexes.

Like the demicrosses, this family exists because, as mentioned above, n-simplices and

n-orthoplexes have, respectively, n−1-simplices and orthoplexes as vertex figures.

The 021 polytope must be, as discussed above, 4-dimensional: as the name

indicates (see also graph in Fig. 10.10), it is the Rectified 5-cell, a semi-regular

polychoron with simplices (Tetrahedra) and orthoplexes (Octahedra) as cells. This is the

vertex figure of a 5-D object with 4-simplices (5-cells) and 4-orthoplexes (16-cells) as

facets: the 121 polytope, the 5-demicube.

Something extraordinary happens next. The 221 semi-regular

polytope has 72 5-simplex and 27 5-orthoplex facets. What is unusual is its symmetry,

which with two distinct branches longer than 1, is quite unlike any we've seen until now;

it is one of 39 uniform

polytopes with E6 symmetry. In seven dimensions, the 321 semi-regular

polytope has 576 6-simplex and 126 6-orthoplex facets. It is one of 127 uniform polytopes with E7

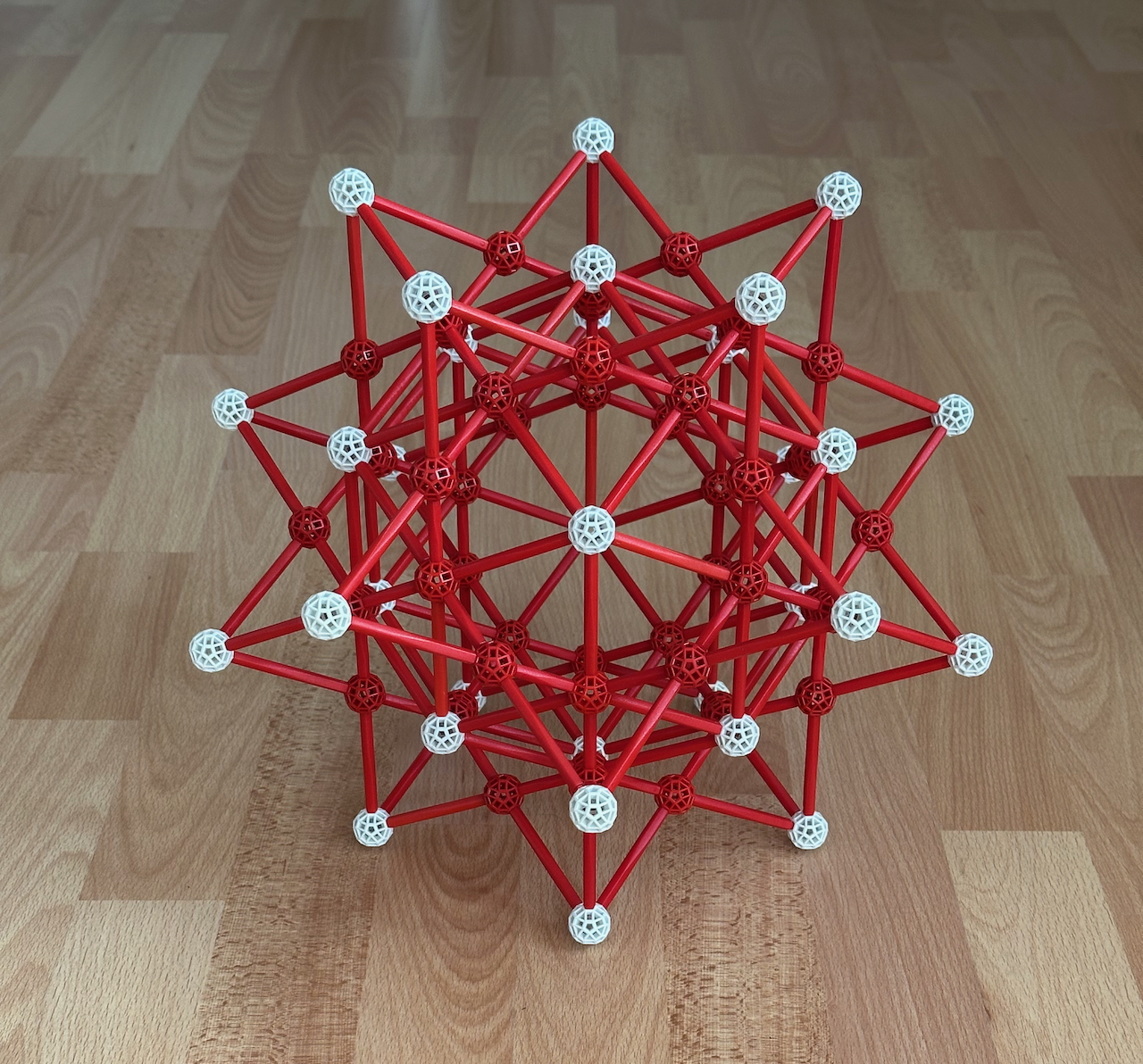

symmetry. Finally, in eight dimensions, the 421 semi-regular

polytope (see Figs. 10.11 and 10.12) has 17280 7-simplex and 2160 7-orthoplex facets.

It is is one of 255

uniform polytopes with E8 symmetry. The number of fundamental simplexes in

the E8 kaleidoscope is 696,729,600!

That's it! Unlike in the case of the demicrosses, the family ends, because its next member

has an angular defect around each vertex of zero, being therefore a tesselation of the 8-D

space, the 521 honeycomb. The fact

that it is infinite implies that it cannot serve as a vertex figure for any higher-D

polytope. From this, we conclude that the E6, E7 and E8

symmetries are also exceptional objects!

Merely by rearranging which branch is ringed in the CD graphs of the k21

family in Fig. 10.10., we obtain the 2k1 and 12k

polytope families, which include the exact same symmetries, both of which start with the

5-cell.

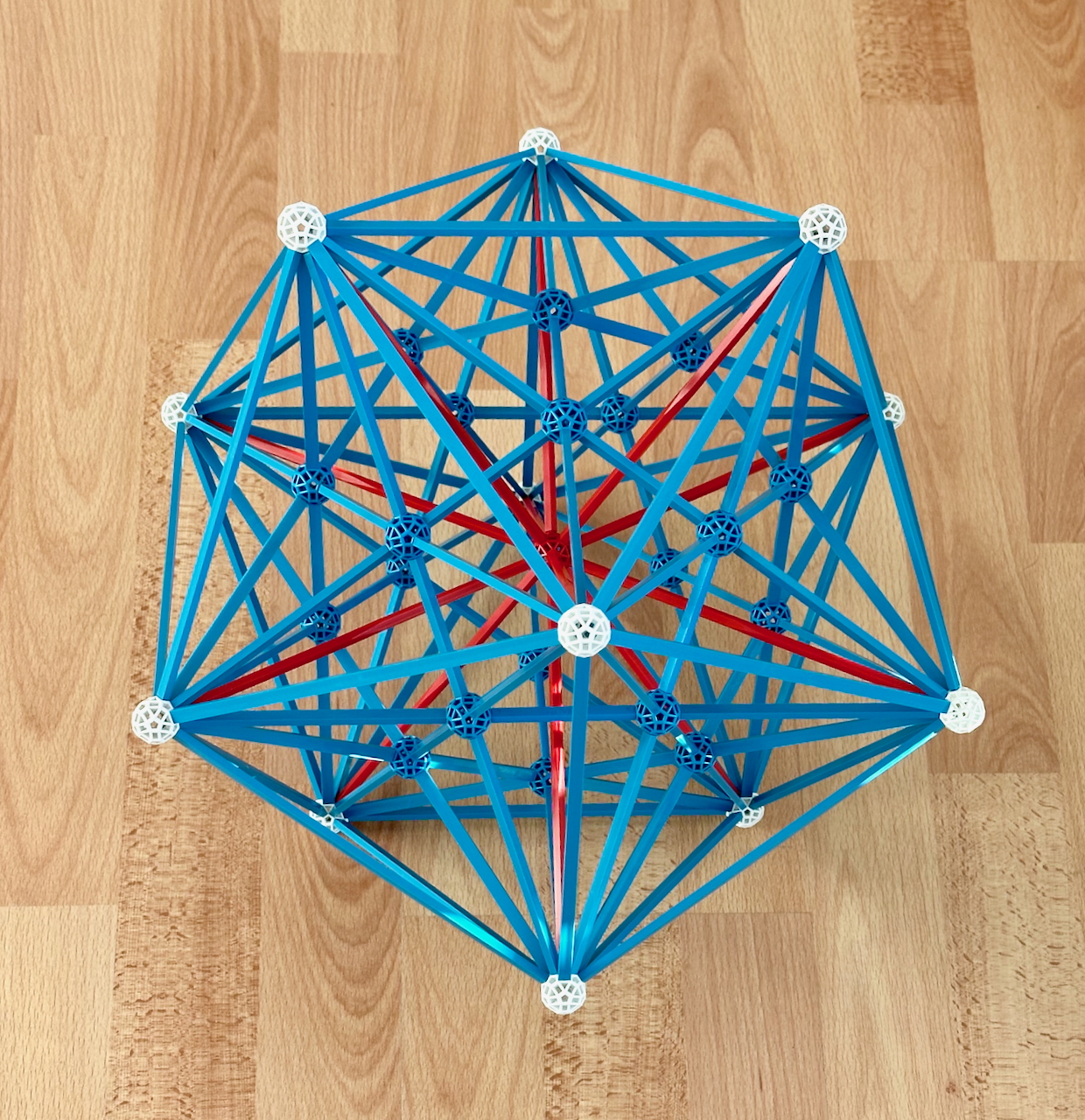

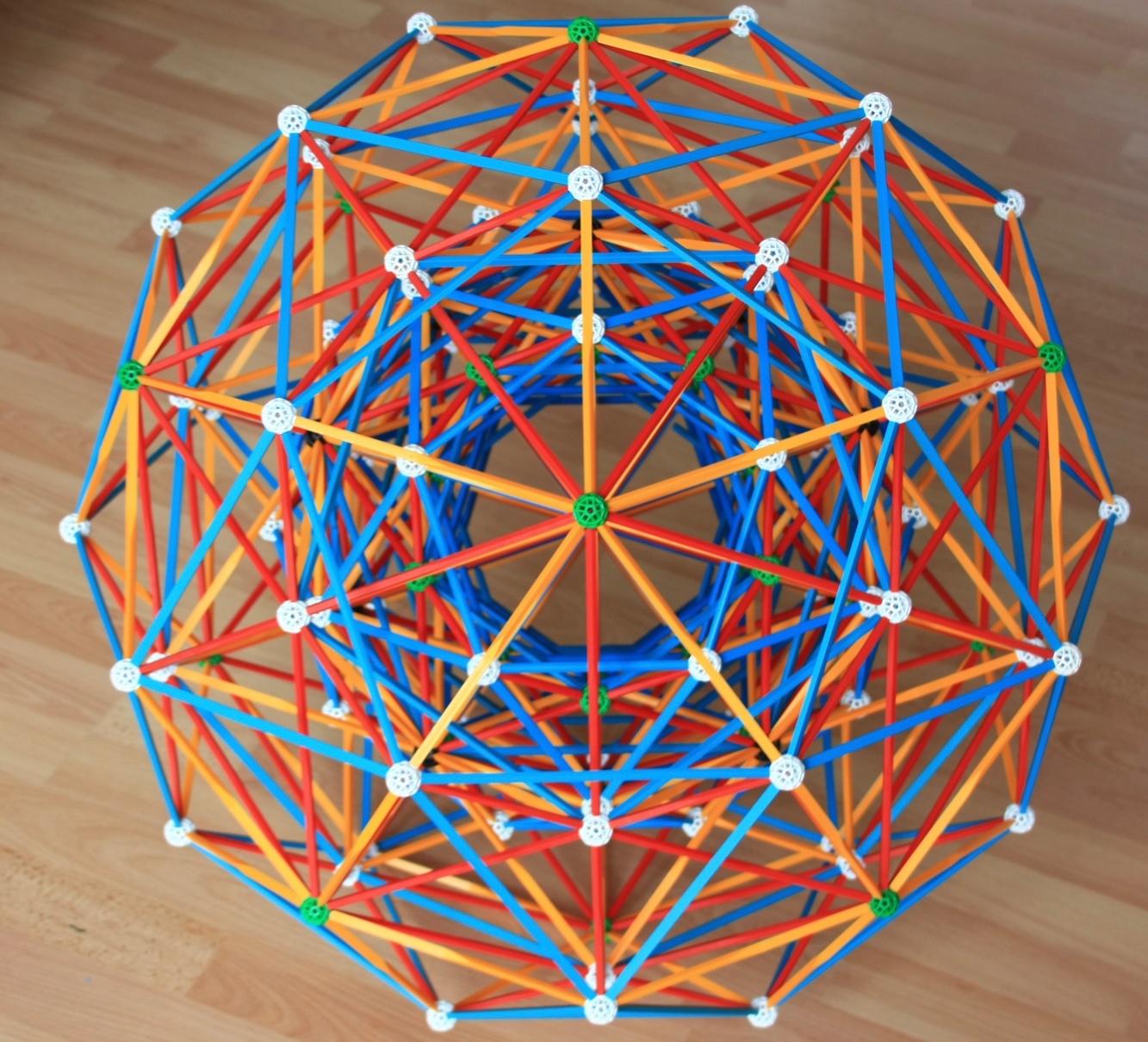

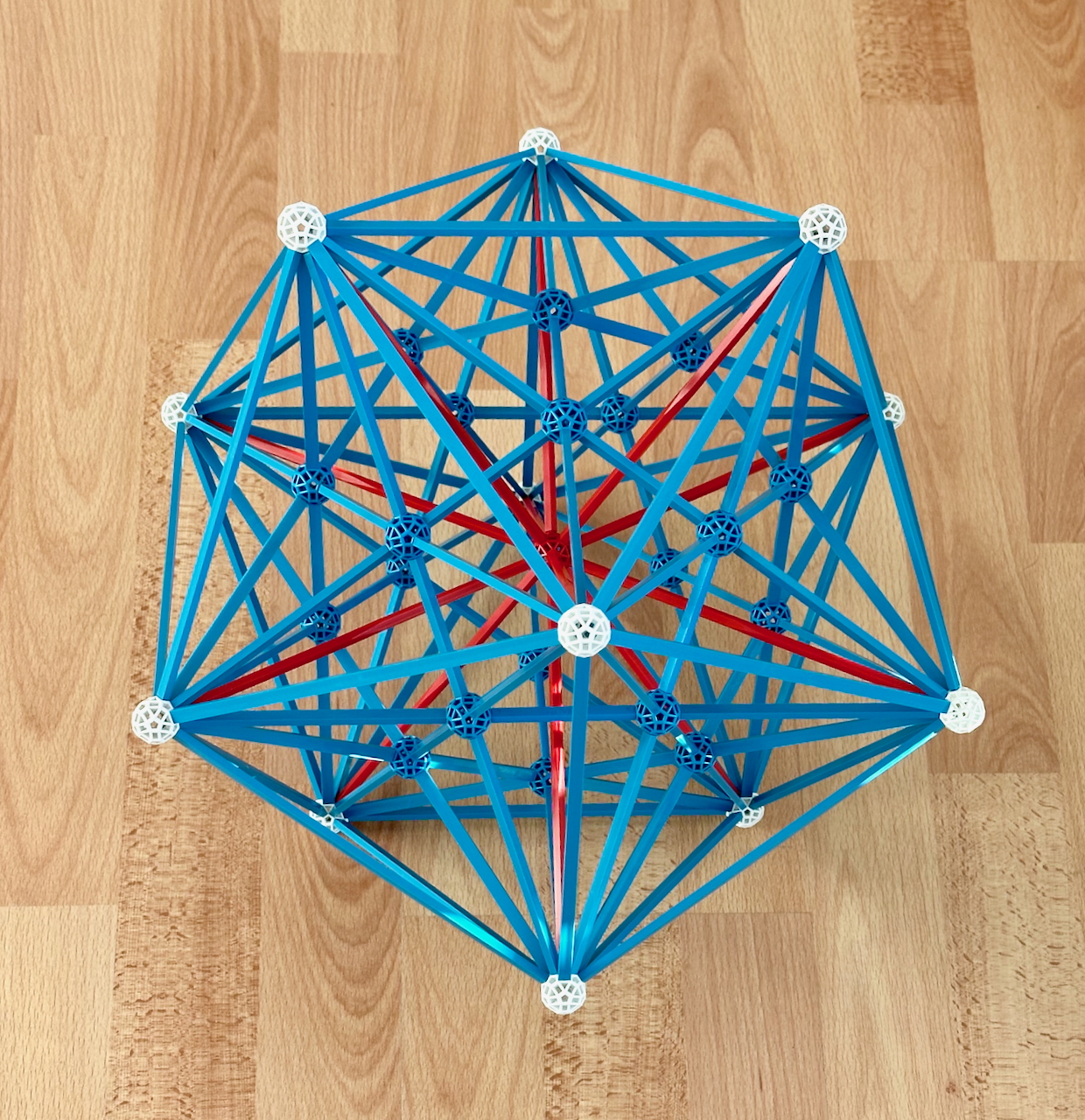

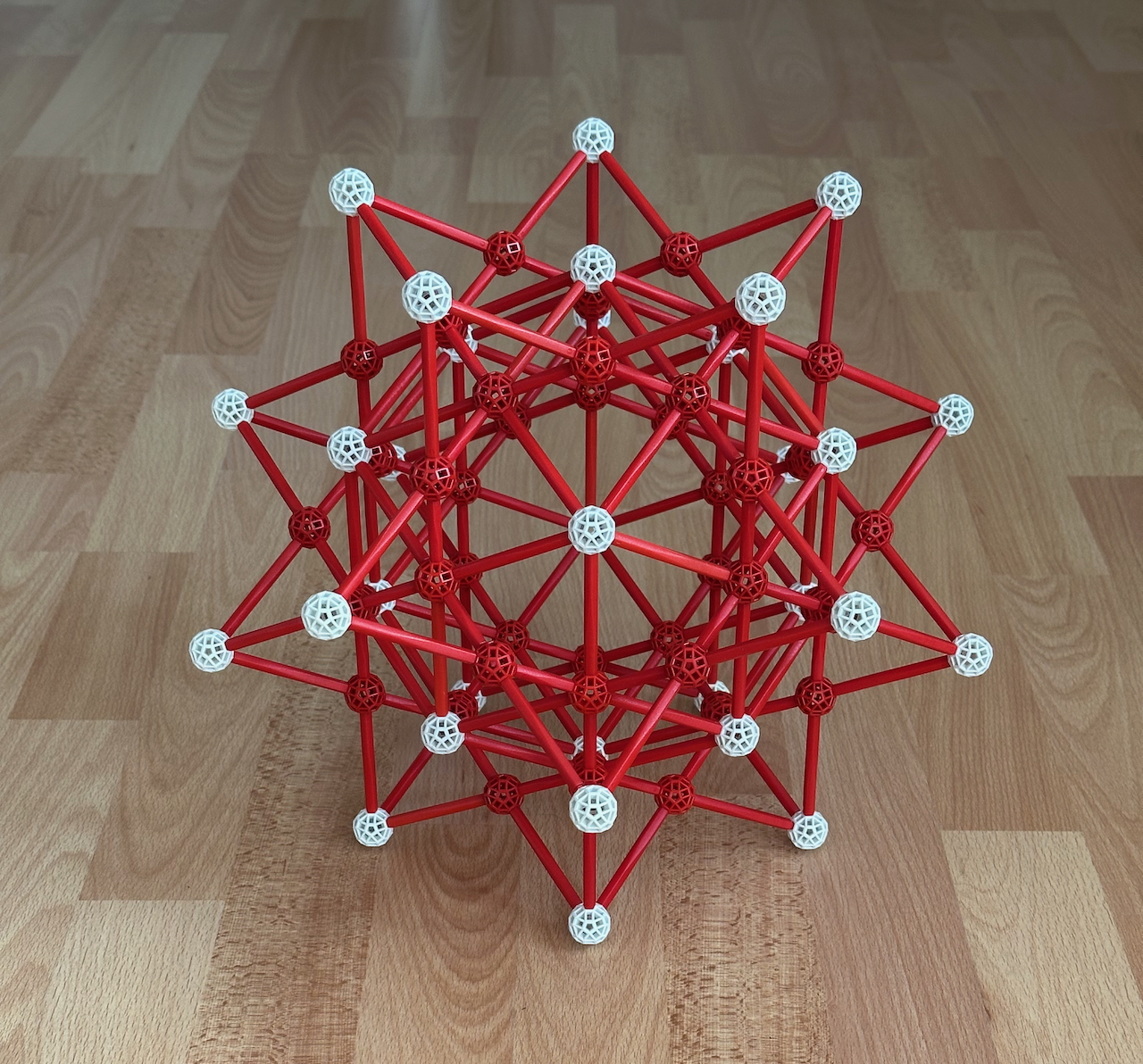

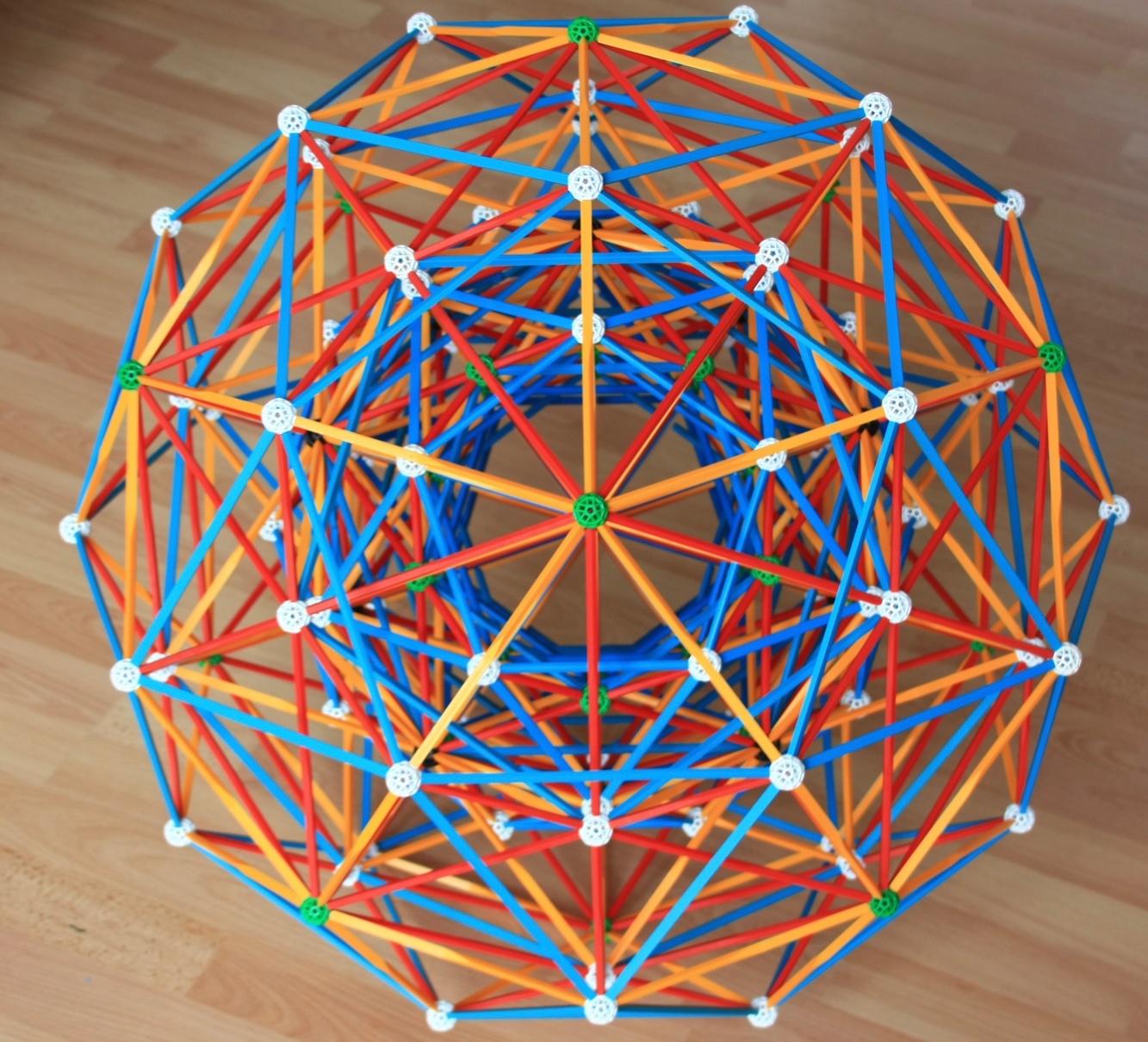

Fig. 10.11: A Zomable projection of the 421 polytope.

This model required 120 B3s, 60 R3s and 120 Y3s. Alternatively, the model can be made on a

smaller scale.

Fig. 10.11 shows a Zomable projection

of the 421 polytope that has Icosahedral symmetry. However, and importantly, it

also represents a projection of the 421 polytope to 4-D space that has the

Hexacosichoric symmetry of the 600-cell. This is highlighted by the fact that the 240

vertices project here as the 2 × 120 vertices of two concentric 600-cells, with one

of them being larger than the other by a factor of φ. The reason for this is explained

in detail here.

It is not possible to project all 6720 edges into a 3-D Zometool model: in this

projection, they are all Zomable, but they just have too many intersections. Therefore, we

must choose a subset of edges to represent. In this model, we use a beautiful fact, that

projection of the 421 polytope into 4-D space also contains all 2 ×720 =

1440 the edges of those two concentric 600-cells.

For more on Zomable projections of k21 polytopes, check this vZome page. For a physical

Icosahedral projection of the 421 polytope with all edge directions

represented, see Fig. 10.12.

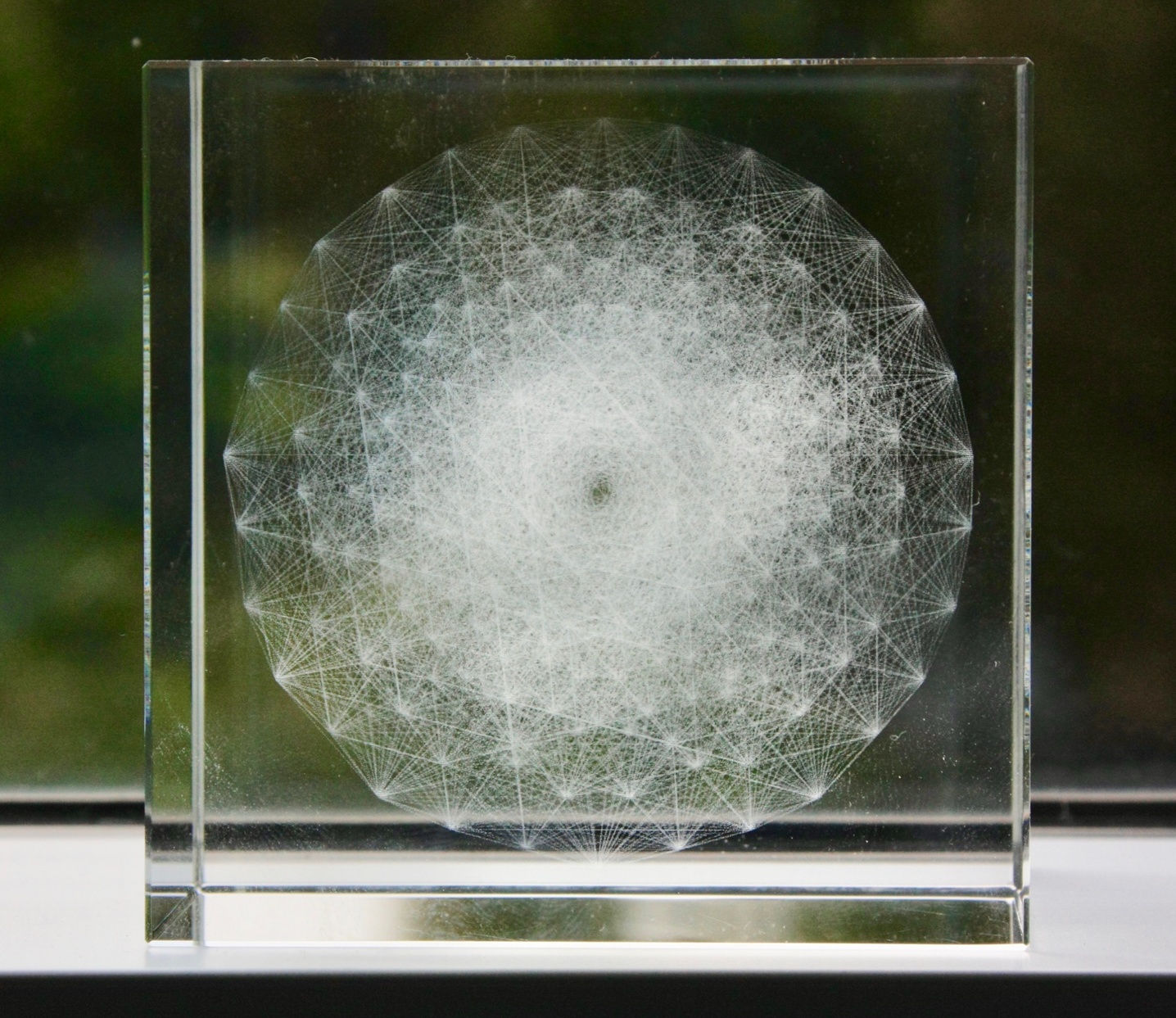

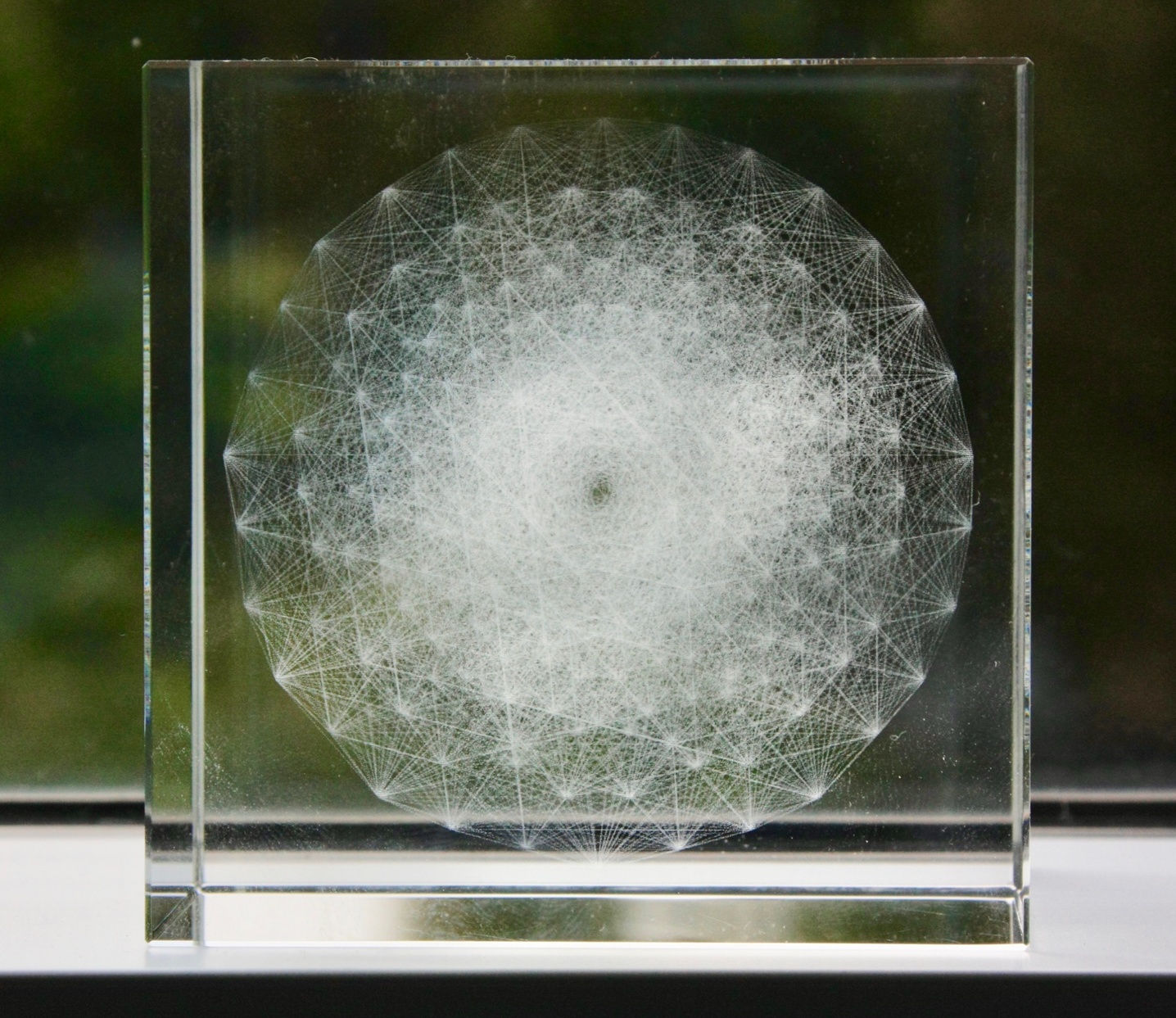

Fig. 10.12: An orthographic projection of the 421 polytope in 3-D space, now

with all the edges represented. This model is laser-engraved in glass.

The polytopes depicted in this page have a dense set of geometric relations. This is

highlighted by the fact that, in addition to the previous polytope families, there are

several others, which include the same polytopes and generally the same symmetries. For

instance, the 5-simplex alone belongs to 3 different multi-dimensional polytope families

that start in 5 dimensions, where it is the case with k = 0:

- The 13k polytope family. The 6-D member, the 131 polytope, is

the aforementioned 6-demicube. The 7-D member, the 132 polytope, is one of

the aforementioned 127 uniform polytopes built with E7 symmetry; it facets are

122

polytopes and 6-demicubes. The family ends with the 133 honeycomb of 7-D

space; this has only one type of facet, the 132 polytope.

- By changing which branch is being ringed in the CD graphs of the last family, we

obtain the 3k1 polytope family, which has the same symmetries. The 6-D member,

the 311 polytope, is the aforementioned 6-orthoplex. The 7-D member is the

aforementioned 321 semi-regular polytope. The family ends with the 331

honeycomb of 7-D space, which has 321 and 7-simplex facets and the same

symmetries as the 133 honeycomb.

- The 22k polytope family. The 6-D member is the aforementioned

221 semi-regular polytope. The family ends with the the 222 honeycomb of the

6-D space, which has only one type of facet, the 221 polytope.

The last rearrangement of the first two families is the k31 family (where, as

it should be clear by now, each polytope is the vertex figure of the (k+1)31

polytope). The 031 polytope is the rectified 5-simplex. The

131 polytope is the 6-demicube. The next member is the 231 polytope, which has

221 and 6-simplex facets. This ends with the aforementioned 331

honeycomb.

Given the symmetry of the numbers, the only rearrangement of the third family is the

k22 polytope family. The 022 polytope is the

birectified 5-simplex. The 6-D member is the 122 polytope, which has

5-demicube facets. This ends with the aforementioned 222 honeycomb.

With these last families, all the unusual "Wythoff-regular" polytopes and their honeycombs

in 6, 7 and 8 dimensions are listed.

Paulo's polytope site / Next: References