Pulsar orbits the period-acceleration plane

Paulo C. Freire, M. Kramer and A. G. Lyne

Introduction

The discovery of a pulsar whose period changes significantly during the observation usually indicates that it is a member of a binary system. It is then important to determine the Keplerian orbital parameters of the system in order to investigate the astrophysics of the two stars and to obtain a coherent timing solution for the rotation of the pulsar.

The usual procedure for obtaining orbital parameters involves fitting a Keplerian model to a series of period measurements specified in time. Such a procedure works well, provided that it is possible to determine the rotational period on several occasions during a single orbit. However, there are often circumstances where this is not the case, such as where interstellar scintillation permits only sparse positive detections of a pulsar. This is the case of most of the millisecond pulsars in 47 Tucanae.

In what follows, we present a simple procedure for estimating the Keplerian orbital parameters of a binary that is completely independent of the distribution of the epochs of the individual observations. The only thing that is required is that the period derivatives (or accelerations) are known in each observation. Estimates of accelerations or period derivatives are normally provided by acceleration surveys, and can be easily refined using the technique of pulsar timing

We first present the equations for the period and acceleration of a pulsar in an eccentric binary system as a function of its position in the orbit. We then provide an analysis of the circular case. In Freire, Kramer & Lyne (2001) (from where most of this text and following equations are taken), we describe in more detail how circular binary orbits can be determined from the observed periods and accelerations of the pulsar.

Binary orbits in the acceleration/period plane

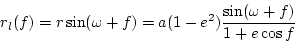

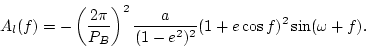

Figure 1 represents, (

ERRATUM (published here): Note that the last term in this equation includes a

The time derivative of

| (2) | |||

| (3) | |||

|

(4) |

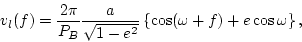

we obtain:

where

if the total velocity of the pulsar,

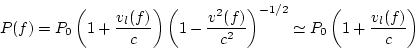

Differentiating equation 6, we obtain the acceleration of the pulsar along the line of sight:

| (7) |

This is how we convert the period derivatives to accelerations.

Differentiating equation 5 in time, we obtain

Plotting

Circular Orbits

The vast majority of Galactic binaries containing "true" millisecond pulsars, i.e., those with periods below 20 ms, have rather circular orbits (see, e.g., the ATNF Pulsar Catalog). For these, we can setand

The track followed by such pulsars in the period/acceleration space is thus an ellipse centred on the point (

47 Tuc W

47 Tuc S

47 Tuc T

Inf Figure 3, we can see that these equations describe perfectly the observed periods and accelerations of two pulsars with hitherto unknown orbits (47 Tuc T and 47 Tuc S), and of a previous pulsars with a known orbit (47 Tuc W). The method used to determine the best ellipse fit is described in the Appendix of Freire, Kramer & Lyne (2001). Once this fit is done we can easily recover the two relevant orbital parameters in a circular orbit from the best ellipse's

Using these newly determined orbital parameters, we can calculate the angular orbital phase for each

Since the time

We can use these values to achieve the correct orbit count between any two observations. One metod of doing this is descibed in Freire, Kramer & Lyne (2001), another more intuitive method is described in Chapter 4 of my Ph.D. Thesis (.ps.gz,.pdf.gz).

Summary

The equations above describe only the mathematical principles of orbit determination from observed barycentric periods and accelerations. For practical algorithms that solve the circular case, please refer to Freire, Kramer & Lyne (2001), particularly to its Appendix.Using these methods, we can find the orbital parameters of any binary pulsar, no matter how badly under-sampled, as long as the accelerations are measurable. But this method is useful in a more general situation. It can provide a scientifically sound starting point in a "Time-Period" fit, even when the orbit is reasonably well sampled. Until now, this starting solution always involved some degree of guessing.

Imprint / Privacy policy / Back to Paulo's main page.